“Wait till you’re 21! Only then you can talk about politics! Now, whatever you say and think does not matter!” my cousin’s husband (at that time) angrily retorted at me. He was upset that I questioned the basis of his loyalty to the Malaysian Indian Congress (MIC).

I was disappointed that I didn’t get to find out how he could possibly make the case that a party so plagued by numerous corruption scandals was the only saving grace for the Malaysian Indian community.

Our argument would come to an uninspiring end because my cousin interjected with “Okay, that’s enough political talk for now!”, seeing how embarrassing it was for her party guests to witness a 30-year-old man, a former political aide, get so riled up by her 18-year-old cousin.

Years down the road, I came to learn that “Wait till you’re 21” was a yardstick to determine the extent to which young Malaysians like myself could play a role in politics and nation-building.

That little tiff had very much informed my understanding of youth political participation in this country. Our worth as political subjects was determined by the voting age.

So when July 16, 2019, happened, I saw it as a great blessing for Malaysians who are younger than me. Unlike me, they wouldn’t have to wait for their 21st birthday to be eligible to vote in the next general elections.

Their hopes and dreams for the governance of Malaysia are now recognised. Upon turning 18, they are now going to be automatically registered as voters. They will even have the chance to stand as political candidates in their own right.

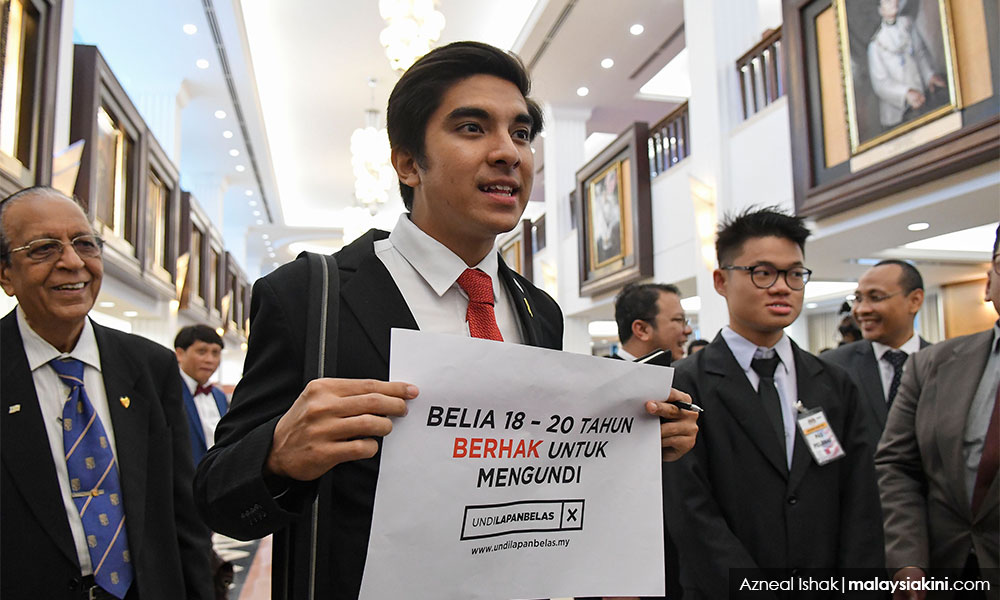

Now, this is what I would call a real conversation about “Malaysia Baru”. Thanks to the tireless efforts of Undi 18 campaigners, Qyira Yusri and Tharma Pillai, as well as the support of our Youth and Sports Minister, Syed Saddiq Syed Abdul Rahman (above), the 211 members of Parliament made a historic move to pass the Undi 18 bill, and amend the Federal Constitution.

This shows that Malaysian politicians on both sides of the divide, even in all their seniority, are in agreement that the youth need to be given more space in the democratic process.

In spite of this, there are still members of the public who cannot help but have reservations about lowering the voting age. As I surveyed Twitter to find out why, it was disheartening to discover fears of young, naïve voters being courted by far-right nationalist or religious interests. While others described the possibility of a reduced commitment to policy-based reform, as one too many millennials are fixated on their own lifestyles.

It was even more disappointing to find out that among those who hold such views are a number of 18-year-olds!

Such apathy must be addressed quickly if we are going to elevate political discourse in Malaysia. As my work with Imagined Malaysia has taught me, a lot of the anxieties that we experience in national politics can often be addressed by looking back into our past.

Since we are now in a very exciting time as a country, it is important that young Malaysians critically engage in our own history. It will allow us to locate our own voice as political subjects and be able to root its legitimacy. That way, there wouldn’t be room for a logical fallacy, such as the legal age requirement being the only source of validation for youth political agency.

As a student of history, my greatest pet peeve about our official historiography has always been the exclusionary nature of what we call “the Merdeka narrative”. Postwar political parties such as the United Malays National Organisation (Umno), Malaysian Indian Congress (MIC) and Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA) consist of middle-aged British educated local elite.

These men have come to be recognised as the founding fathers of Malaysia. Because their stories take centre stage in our school History textbooks, and they continue to be postulated as the sole victors building the nation, there is hardly any mention about the significant role played by youth in mobilising the desire for self-determination.

As a result, we have done a great injustice, not just to memories of youth movements in our past, but also to a fiery generation of scholars, activists and politicians who were once critics of the state of Malaysia’s education system and its paternalistic treatment of the youth.

Throughout the course of Malaysia’s modern and contemporary history, there have been individuals who took part in the contest for power and influence that would formulate their idea of Malaysia as a “nation”. Many of whom were actually relatively young.

It may be difficult to ascertain how many of them began their engagement in youth politics before turning 18, but there are two particular cases that I can think of that are very convincing.

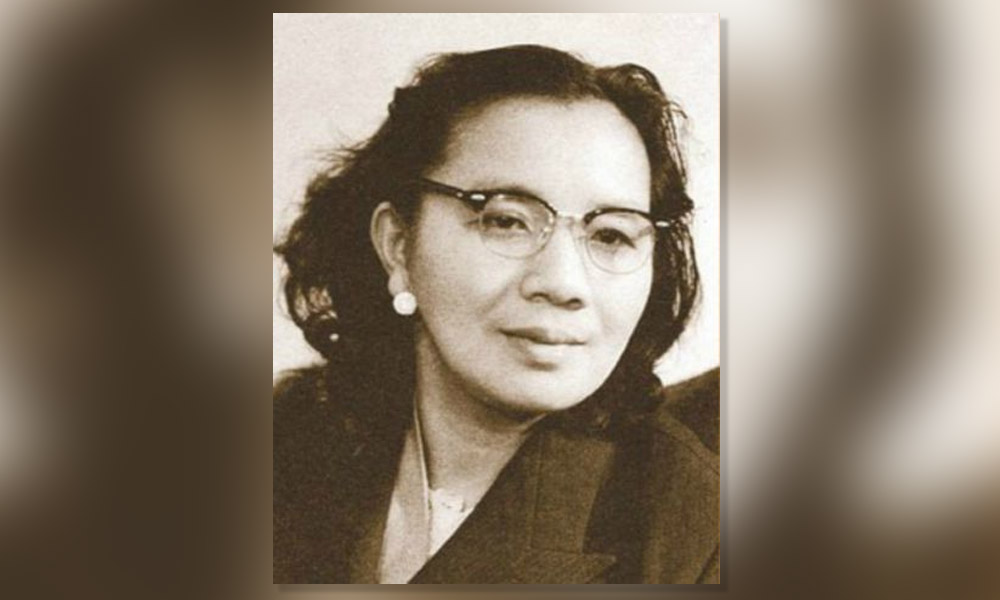

One is the late Shamsiah Fakeh (above). In her memoir, she described her fervent pursuit of knowledge during her studies at the age of 16, under an influential Muslim reformist, Lebai Maadah.

In spite of not being able to escape the constraints of early marriage, Shamsiah continued to develop her political convictions, especially through witnessing the events that transpired during the Japanese occupation.

A charismatic orator, she was later recruited into the country’s first Malay nationalist party, Parti Kesatuan Melayu Malaya (PKMM) and became the leader of its women’s wing in 1946. She was only 22 years old.

The second is P Veerasenan, the vice-president of the Pan-Malayan Federation of Trade Unions (PMFTU). While very little is known about him, this notable trade unionist continues to be remembered as an important mover in organising the 1940s labour movement in Malaya, alongside individuals like SA Ganapathy and Abdullah CD.

Upon the banning of the PMFTU in 1948, Veerasenan was forced to hide to avoid arrest and deportation, although he eventually ended up being captured and killed. Veerasenan, too, was 22 years of age.

Yet, both Shamsiah and Veerasenan do not appear in the dominant memory of Malaysia’s political developments. Like the vibrant waves of student activism from the 1960s and right up to the 1990s, they, too, have been relegated to the periphery of our imagination.

Narratives about these movements largely have been largely from the public eye due to the narrow scope of political discourse dictated by those who claim authority.

According to the political scientist Meredith Weiss, this phenomenon has been credited to Barisan Nasional’s governance. She described the regime as one that was a “rapidly consolidating, decreasingly liberal state” which dealt harshly with the movement, even as they sought to expand higher education to accelerate economic development.

While it is normal to have apprehensions about political immaturity in a time where democracy is facing a global decline, we shouldn’t be too quick to assume that the worst is about to come with this change.

This is certainly the case when we contemplate the centrality of young Malaysians in determining a democracy that is healthy, thriving and inclusive.

The philosopher Jacques Derrida said that democracy is inherently a concept that is constantly being challenged. It is often at odds with itself in an effort to continuously improve.

Due to this, we are constantly working for “democracy to come”, where much of the hopes and dreams that inform our political developments rest on optimism that society and government are committed to positive changes in the present and future. Democracy is a destination that we are constantly journeying towards.

The contributions of young Malaysians have had a major impact in enhancing the role of civil society in shaping political discourse. If the 1940s to 1950s are examples that are too dated for one’s taste, then the fact that 41 percent of the voters during the 14th general election were between the ages of 21 and 39 should speak for the capability of youth to preserve Malaysia’s democratic welfare.

So, Undi 18 is not just a spontaneous idea that emerged from nothing. It is an indisputable and inevitable product of Malaysia’s legacy of youth politics.

NETUSHA NAIDU is the co-founder of Imagined Malaysia, an NGO dedicated to the promotion of historical education among young Malaysians. She is currently pursuing her post-graduate studies in Southeast Asian history at St Catharine’s College, University of Cambridge. - Mkini

GENUINE LOAN WITH LOW INTEREST RATE APPLY

ReplyDeleteDo you need finance to start up your own business or expand your business, Do you need funds to pay off your

debt? We give out loan to interested individuals and company's who are seeking loan with good faith. Are you

seriously in need of an urgent loan contact us.Email: creditloan11@gmail.com

BORROWERS DATA FORM

1)YOUR NAME:_______________

2)YOUR COUNTRY:____________

3)YOUR OCCUPATION:_________

4)YOUR MARITAL STATUS:_____

5)PHONE NUMBER:____________

6)MONTHLY INCOME:__________

7)ADDRESS:_________________

8)PURPOSE:_________________

9)LOAN REQUEST:____________

10)LOAN DURATION:__________

11)CITY/ZIP CODE:__________

12)HAVE YOU APPLIED FOR LOAN BEFORE?