A QUESTION OF BUSINESS | Without a doubt the ringgit is historically rather weak even if the economy still continues to grow at a relatively healthy pace - the latest figures show a good growth of 5.8% for the second quarter of the year.

Full year growth of gross domestic product (GDP - the sum of goods and services produced) is expected to be a respectable 5%, considered to be still healthy given the current environment. Despite 1MDB and other issues, the country’s finances are expected to hold out in the short term.

So why does the ringgit remain weak, trading at levels which are weaker than at the height of the 1997/98 Asian financial crisis? What is it that is happening that keeps the ringgit level depressed?Perhaps it is due to a risk premium on the ringgit following the emergence of kleptocracy (re: 1MDB where as much as RM40 billion could be at risk as thieves dip their fingers into money borrowed by a government company via bond issues) or apprehension over the ongoing spate of mega projects (re: the RM55 billion East Coast Rail Link whose cost may go to over RM100 billion.

It may be that people fear that the future of the country will be affected by kleptocracy and a dishonest government that may put the economy in grave danger in years to come. Unless such a perception lifts through a change in government or definite shift in policies and implementation, the capital markets are going to place a lower value on the ringgit to compensate for that extra risk - the kleptocracy risk premium.

The movement of the ringgit over the years tells an interesting, compelling story. Up until the early 70s, the exchange rate of the ringgit was fixed but when the world moved largely to floating rates, the ringgit as well as the Singapore dollar actually performed well initially - up to about 1980.

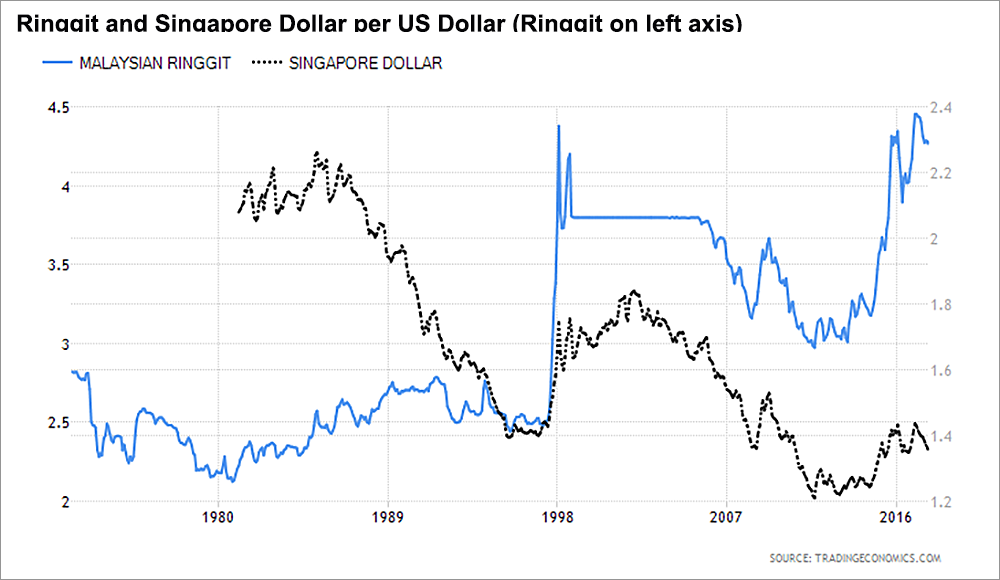

The chart and the table show that in 1980, the ringgit and the Singapore dollar had nearly the same value as the ringgit. But that changed as Dr Mahathir Mohamad became prime minister in 1981 which saw a precipitous decline of the ringgit relative to the Singapore dollar even though it held steady against the US dollar until the 1998 Asian financial crisis.

That meant the Singapore dollar was appreciating against the US dollar. Singapore obviously did not pursue a weak currency policy and allowed its currency to appreciate in the belief that the economy could compensate by having higher value-added industries and services.

Malaysia under Mahathir however opted for cheap labour, allowing unrestricted imports of labour, often illegal, from Indonesia, Philippines and later Bangladesh. Manufacturing tended to be on lower value-added such as assembly of electronics.

The Asian financial crisis of 1997/98 saw the ringgit collapsing to as low as 4.71 ringgit to one US dollar from pre-crisis levels of around 2.5, a level it has never since achieved although it strengthened to around 3.0 during the world financial crisis in 2009, which coincided with Najib Razak becoming prime minister. Currently, the ringgit at around 4.3 is weaker than the pegged exchange rate of 3.8 imposed in 1998, at the height of the crisis.

In contrast, while the Singapore dollar fell (see chart) in 1998, the fall was less and the currency is now significantly stronger than it was in 1998. While the Singapore dollar is clearly strengthening over the last few decades, the Malaysian ringgit was in a steady decline.

While the Singaporean and Malaysian currencies were on par right up to around 1980 - indeed in the two countries, they were exchangeable for one another - it changed after that. Over the next 37 years or so, the two currencies moved terribly out of line and the Singapore dollar is now worth over three times the ringgit.

This has broadly reflected the widening gap in economic development between Malaysia and Singapore, with Singapore far outpacing Malaysia in all areas including educational levels, infrastructure, GDP per capita, quality of life etc, etc.

A symptom of a larger illness

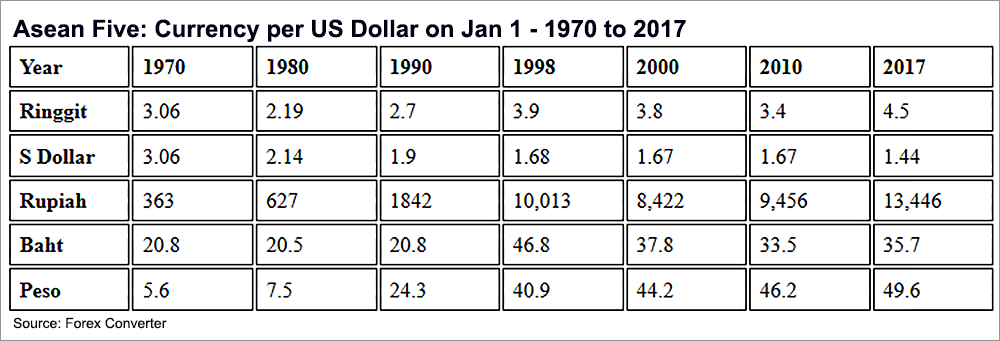

What about the other Asean countries? The table, compiled by using figures from this converter shows the value of the Asean five - Malaysia Singapore, Indonesia, Thailand and Philippines - currencies in terms of the US dollar between 1970 and 2017, a period of 47 years.

It is a mark of the failure of the Asean Five barring Singapore that all of them have currencies which are much weaker in 2017 than the US dollar 37 years ago, in 1970. One US dollar today gives you 50% more ringgit, an astounding 36 times (3600%) more Indonesian rupiah, an incredible eight times (800%) more Philippines peso and 70% more Thai baht. For Singapore, one US dollar only gets less than half what it did before, reflecting the much-increased purchasing power and hence wealth of the Singaporeans.

That’s not all, between 2010 and 2017, coinciding with Najib Razak’s reign as prime minister, the ringgit declined the most after Indonesia, with the major loss coming in the last two years. From 2015, the ringgit was the worst performing currency by far among the Asean Five declining by nearly 30%.

This was the period when the 1MDB scandal unravelled and the mega projects related to China began to progress.

It is worthwhile noting that the currencies of Indonesia and the Philippines lost the most during the reign of two kleptocrats, respectively President Suharto (1967-1998) and President Ferdinand Marcos (1965-1986). These countries still have not recovered from the damage done by these two kleptocrats.

Currency weakness is a symptom of a larger illness. If the disease is not treated and the rot is not stopped, the ringgit will keep on sliding lower and will impoverish Malaysia on a relative basis for many years to come.

The bottom line, after taking into account short-term fluctuations, is that a country which is doing well economically and has in place the right policies to foster the competitiveness of its people through a variety of measures which includes excellent education, infrastructure, good governance, integrity and competence amongst others, will see its currency appreciate.

Up to about 1980, we were doing well as a country. Even after the May 13, 1969 racial riots which resulted in suppression and ad hoc policy making and worse implementation, our broad economy improved and the currency strengthened. Note, we were about par with Singapore in 1980.

And then the rot set in firmly and we have been on a long decline which started with the Asian financial crisis of 1997/98 but unlike Thailand and Singapore, whose currencies are now stronger, we have regressed.

The ringgit’s value and weak trend is nothing but a reflection of Malaysia’s poor future economic fundamentals and represents effectively a huge risk premium for kleptocracy and all that means for the future of the country.

P GUNASEGARAM, an independent writer and consultant, can be contacted at t.p.guna@gmail.com. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.