As Umno members meet in the party’s general assembly to discuss the party’s future this week, it is important to look at the party’s electoral performance in GE15 in more depth.

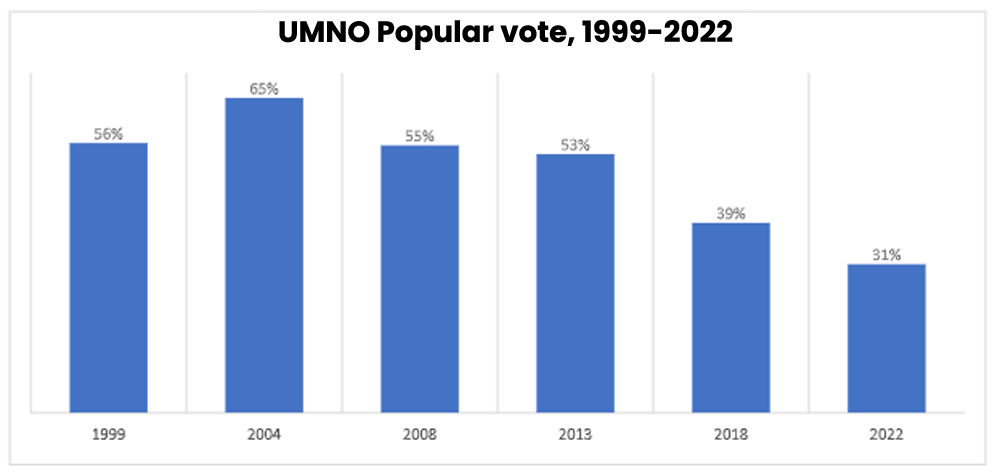

It is well-known that the last general election was the party’s worst performance in history. The party only managed to win 27 seats and 31 percent of the popular vote.

What is not fully appreciated is the variation in performance and factors that accounted for the results, beyond the general view that poor leadership by party president Ahmad Zahid Hamidi and miscalculation on calling early election by party vice-president Ismail Sabri Yaakob brought the party to its electoral knees.

This piece looks at Umno’s electoral performance in GE15 by examining trends since 1999. It also outlines factors that contributed to the party’s electoral defeats, suggesting that both longer-term and a mismanaged campaign were at play.

Umno protest vote

One of the most important lenses to understand GE15 is that the election result was an Umno protest. Both Pakatan Harapan and Perikatan Nasional (PN) focused their campaigns on Umno and voters left the not-as-grand party behind in droves. Umno also did not attract the same level of younger voters as in the past.

An electoral decline has been a trajectory for the party over the last four general elections since 2004. Umno’s losses in terms of popular votes in GE15, a drop of 9 percent, were not as significant as the Najib Abdul Razak-led election of 2018, where the party lost 14 percent.

Yet four compounded negative performances had a toll on the party, and the recent GE15 losses were enough to lose the party seats, from a high of 102 seats in 2004 to a paltry 27 seats in the latest election. This outcome is an electoral collapse.

To appreciate the scope of the losses, one can look at the performance in Umno’s traditional ‘core’ seats, those that the party has won consistently since 1999. At Umno’s core, the party lost 24 seats, a devastating hollowing out of the party’s political base.

These seats include Padang Besar and Arau in Perlis; Kepala Batas and Tasik Gelugor in Penang; Gua Musang in Kelantan; Besut and Hulu Terengganu in Terengganu; Jerantut, Maran and Rompin in Pahang; Grik, Kuala Kangsar, Larut, Padang Rengas, Parit and Pasir Salak in Perak; Sabak Bernam and Tanjong Karang in Selangor; Putrajaya; Jasin and Masjid Tanah in Malacca; Mersing in Johor and Sipitang, Kudat and Beluran in Sabah.

Varied results

Not all of the party’s electoral fortunes were negative everywhere. There were a few gains for Umno, as it managed to win back seats in its traditional core in Negeri Sembilan and Sabah.

These seats include Kuala Pilih, Tampin and Kalabakan. The party also won in Putatan, which had been held by PKR since 2018 and before that was part of BN held from 1999-2018 by Upko. The party also won back two other seats it lost in 2018, Simpang Renggam and Titiwangsa.

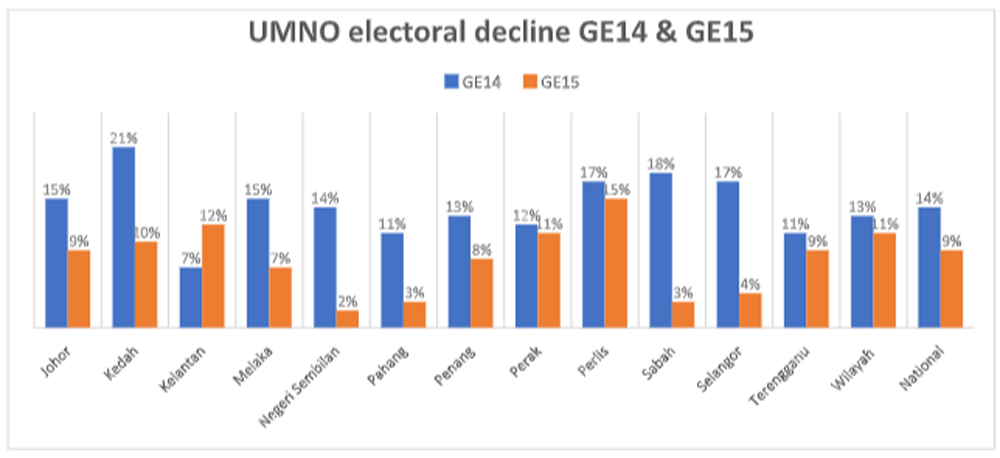

The party performed the best in Negeri Sembilan, where the election was led by party deputy president Mohamad Hasan, now defence minister, only losing a modest 2 percent in the popular vote and picking up two seats.

Umno also did well in Sabah and Pahang, although in the latter it lost more seats. Here the state leadership of Bung Mokhtar Radin and the persistent influence of Najib played a role.

Seat losses were also minimised in Johor, although the party’s popular vote took more of a hit, especially after its strong performance in the March 2022 state polls.

Umno won 43 percent of the popular vote in the March 2022 Johor polls, but only captured 34 percent in GE15, after former chief minister Hasni Mohammad was displaced despite his leadership securing the Johor March 2022 mandate. He won the Simpang Renggam seat handily. Neither state polls victory in Johor nor Malacca translated into strong national performance in GE15.

The worst performance in terms of vote share was in Perlis, a 15 percent drop, the result of party-inflicted damage to remove local warlords.

This was followed by Kelantan, a 12 percent drop, where the party lost all of its seats and in Perak, with a drop of 11 percent. That the performance was so poor in Perak, the home state of party president Zahid, speaks volumes.

A long, deep decline

The variation in the results suggests that there are multiple factors accounting for the outcomes.

A starting point is to recognise that the problems run deep. That the party’s performance has declined over four different elections since 2008, shows that the problems are not the product of one campaign.

The party has long needed meaningful, substantive reform as its leaders have made Umno about themselves rather than the country or its members. The stigma (and reality) of corruption that Umno faces persist. Defending and empowering leaders with corruption and other criminal charges has done the party no favours.

Leaders holding the party captive for themselves has caused harm. The grassroots of Umno have eroded. Sidelining key parts of the party, such as Wanita Umno, has an impact and limited regeneration also has an impact.

Umno leaders’ decisions for ‘survival’ have also been costly. The decision to ally themselves with PAS only served to empower the Islamist party, bringing them into the federal government in the Sheraton Move. The alliance with PAS in 2019 also reinforced conditions that widened ethnoreligious divisions.

Steadily, Umno abandoned the middle ground, leading Malay politics to a more Malay-only ethno-conservative direction. The escalation of racialised rhetoric after 2018 now haunts the party, as they no longer control the Malay narrative and have lost the mantle of being the defender of the Malay community.

In fact, decisions by Umno leaders only brought about its challengers. How the party responded to the 1MDB scandal led to the emergence of Bersatu, which won many of the core seats of the party. Sacking Muhyiddin Yassin has proved to be a damaging decision.

Infighting within Umno has deepened. This factor has long affected Umno electoral outcomes. In the Umno fragmented states of Malacca and Johor, these differences were put aside in 2021 and 2022 respectively, yielding stronger electoral performances.

By contrast, GE15 showcased party divisions, especially the repeated shaming of Ismail Sabri during the campaign and the miscalculated attempts to displace political warlords, notably in Perlis.

The person responsible for these was the party president, Zahid, whose handling of the party in GE15 exacerbated the conflict.

A mismanaged campaign

To say that the campaign was mismanaged is an understatement. There is a long list of issues – how leaders were treated by other leaders, the choice (and displacement) of candidates, the lack of (even) financial support to candidates and the lack of an effective campaign narrative. The disconnect between a campaign call for political stability and the pressure to call an early election, to destabilise the country, was evident.

Despite having one of the best electoral manifestos, these measures were overshadowed by the focus on court cases and corruption. Hubris and ego were on display, as the party leadership assumed a dominant victory only to see it disappear as a result of poor decisions.

Zahid’s assertion of this leadership served as a target that weakened the party, in large part due to a lack of popularity. For those against Umno, he personified the concerns about the party’s decline, notably corruption, and quality of leadership.

A party perceived widely to engage in corruption and having lost heavily from a corruption scandal in 2018 that embraces and opts for a leader facing criminal charges to lead its national campaign should have expected losses.

For many inside the party, Zahid’s role as the party’s defender changed to one of damager in the GE15 campaign. While he alone is not completely responsible for Umno’s GE15 electoral collapse and it was a shared loss – noting also that it was Ismail Sabri who decided to finally buckle and call the election – Zahid was de facto at the helm of the defeat. He made GE15 about himself, as Dr Mahathir Mohamad and Najib did earlier.

A look at the loss of core seats shows that at least half of these could have been better handled. Warlords being cut out without proper consultation in Perlis and Selangor, the placement of Zahid loyalists as candidates, even unpopular ones such as Jamal Yunus in Sungai Besar, or old guard Abd Rahman Bakri in Sabak Bernam, did not help the party. Opportunities to bring in new blood, younger candidates were squandered by ‘Zahid-safe’ choices.

Choosing to publicly punish his 2018 challenger to the party presidency Khairy Jamaluddin only showcased infighting and vengefulness, as the party lost an opportunity to hold onto a seat if he had been fielded in a more competitive area. Self-inflicted party harm was prominent.

The only modest amelioration of this was in Negeri Sembilan and Sabah, where state leaders better managed the local campaigns and local popularity had an impact, especially for Hasan.

Damage levels went beyond the personal. There was a misreading. Zahid’s close ties with PAS which he allied the party with in 2019 blinded him to the challenge that PN was making in GE15.

While Zahid did read the ground of a potential hung Parliament and engaged in talks with Anwar before GE15, the effect of this (to date) and the subsequent follow-my-way-to-power decision to form a unity government has been to reinforce differences inside the party.

Need for contests

Delegates to the Umno general assembly have much to discuss, as it is a painful and pivotal time for the party. It will not be an easy meeting. Hard decisions have to be made, from supporting the decision to be part of the unity government (recently also endorsed by potential president contender Khairy) to party leadership and resuscitation. Coming back from a collapse will not be easy.

What is an easy decision however is the need to allow the delegates a voice to express their concerns, including an option to elect the leaders that they want for the party at all levels.

Leaders should be accountable for their performance, not only in national polls but also in party polls. This is especially the case after Umno’s history during (and after) the Mahathir era has shown that not allowing leadership contests only serves to worsen infighting and weaken the party internally. Umno can little afford either. - Mkini

BRIDGET WELSH is an honorary research associate of the University of Nottingham, Malaysia’s Asia Research Institute (Unari). She is also a senior research associate at the Hu Fu Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies and a senior associate fellow of The Habibie Centre. Her writings can be found at bridgetwelsh.com.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.