It was not entirely unexpected, but definitely unanticipated, that a regime change dawns on Malaysia, retiring the near-unsinkable Goliath, BN, who has had a solid 61-year grip on power in Malaysia since independence.

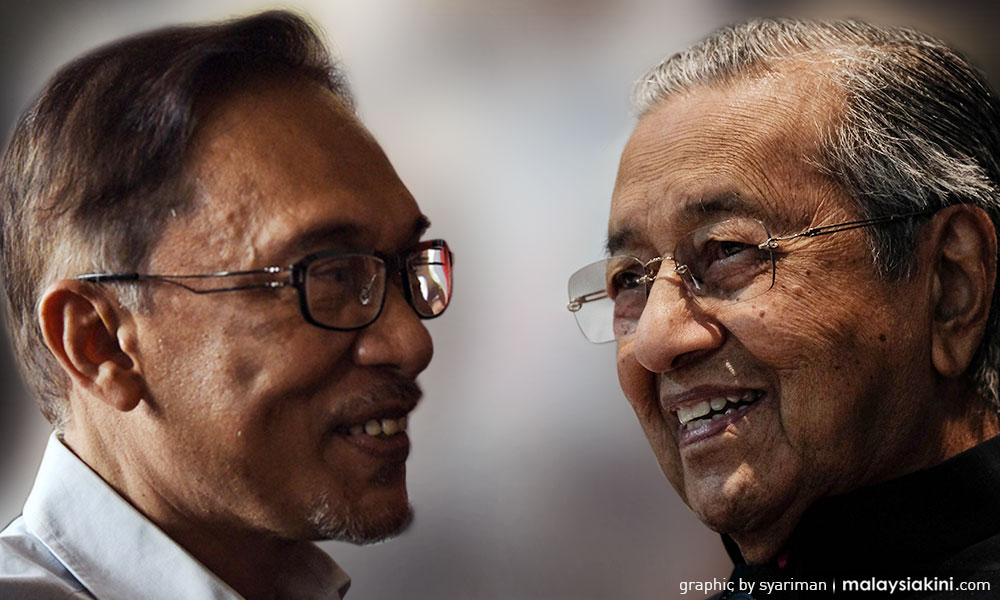

The electoral victory of Pakatan Harapan and the consequent re-entry of former prime minister Mahathir Mohamad into politics cannot but expose a paradox, especially amid the clarion call for holding former ministers accountable for cronyism and abuse of power.

If Malaysia is currently adamant, impatient even, in prosecuting former premier Najib Abdul Razak for his past misconduct, shall it exculpate Prime Minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad of his questionable legacy?

Is Mahathir forgiven and forgivable? Is he more forgivable than Najib due to the distance of time, or more accurately, the limits of our recollection?

Is forgiving Mahathir a courtesy reserved for no one else but his former nemesis, PKR de facto leader Anwar Ibrahim? Is Anwar’s forgiveness the only forgiveness that matters?

I toss these questions into the air and let them tarry without the promise that they are answerable.

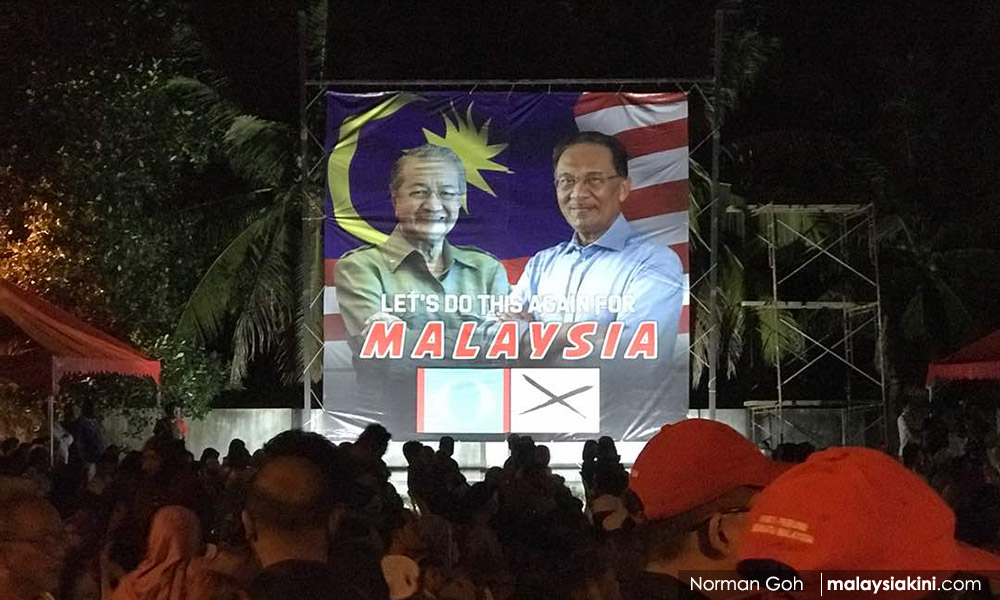

The dogma at present, judging from the many scenes of forgiveness in Malaysia before and after the 14th general election (GE14), is to hasten an answer: to forgive or not to forgive Mahathir. As if forgiveness must be called for to “move on”, to bypass the odd crumbs of history.

But the politics of forgiveness is irreducible to a catechism of pardon or punish; it is not a zero-sum game, it seldom yields a genuine answer, and always it arrives as a response without an answer.

Our fetishism of answer, of answerability, in the form of verdicts and resolutions, now driven by news flash and bite-sized headlines, obscures a paradox in our triumphalism over Mahathir’s return.

In holding a former minister accountable for his previous liabilities while temporarily turning a blind eye to another, an unspeakable threshold is revealed. Where do we draw this threshold where one’s liabilities could pass into forgiveness?

Responding without answering

Today, axiomatic verdicts abound: it is not the right time to question Mahathir’s legacy; forgiveness is necessary for the greater good; it is time to move on; so on and so forth.

These sentiments refuse to engage with politics, politically, right when the stakes are high. But it is precisely in such an unprecedented moment of regime change that one must not be content with answerable questions.

Scenes of forgiveness began two years prior to GE14, revolving around the potential prospect of the uncanny partnership between Mahathir and Anwar.

When the Save Malaysia Movement ("Gerakan Selamatkan Malaysia"), a campaign to unseat Najib, successfully banded the two political rivals, cynicism generally clouded Mahathir’s endorsement of opposition politics. It begged a newsworthy question: Could Anwar forgive Mahathir?

In March 2016, a Channel News Asia reporter attempted to tease out an unequivocal answer from Anwar: “Dato Seri, are you willing to forgive and forget Dr M?” Anwar’s response was not immediate: “I have already forgiven everyone a long time ago. My battle is not personal, it is an issue of institutional reform, it is not against Dr Mahathir or Dato Seri Najib.”

It was a response without an answer. The stakes were raised again a few months after, when Anwar’s daughter, Nurul Nuha Anwar, requested an apology from Mahathir. Against this background, a reporter pestered Anwar with the same devotion for a definitive answer. A verdict was desperately needed. I quote the conversation at length to illustrate the reporter’s hounding:

Reporter: Would you want him (Mahathir) to still apologise to you, since your daughter made that statement?

Anwar: You know, I have explained. Because, the problem is (that) this came as a sudden, I have not the opportunity to speak to my children before that. But now since I have explained to them the circumstances, it’s enough... Of course, we suffered immensely, but then-

Reporter: So you have forgiven him?

Anwar: [responding to another reporter]

Reporter: So you have forgiven him?

Anwar: [continued to ignore the question]

Reporter: Can we take it that you have forgiven him?

Anwar: I have forgiven a lot of people, a lot of things, but my concern is the present. This people at the present should stop this harassment and the injustice.

When this uninspiring video interview was published in September 2016, it was concluded with a disappointing caption: “Anwar however remained vague on whether he has forgiven Mahathir.”

As long as an unequivocal “either/or” verdict was not given by Anwar, the question of forgiving Mahathir would continue lurking in his press conferences.

Forgiveness vs reconciliation

But if we were to take forgiveness seriously, then, one’s willingness to forgive should not be necessitated only by the need for closure.

The eager attention I have hitherto given to the intricacy of forgiving Mahathir may have appeared familiar to those keen on French philosopher Jacques Derrida’s scholarship on forgiveness and political responsibility.

“Each time forgiveness is at the service of a finality […], each time that it aims to re-establish a normality,” Derrida claims, “then the ‘forgiveness’ is not pure - nor is its concept”.

To complicate political forgiveness, Derrida deems it theoretically necessary to distinguish between forgiveness and reconciliation. If one forgives only to reconcile, one has not forgiven; forgiveness as such is only a “calculation” that is “politically necessary”.

In the case of Anwar, his forgiveness is a much sought-after closure. For an act as intimate as forgiving another, it has now become a political necessity, regardless of Anwar’s personal determination. For the sake of finality, forgiveness has to be forced down the throat.

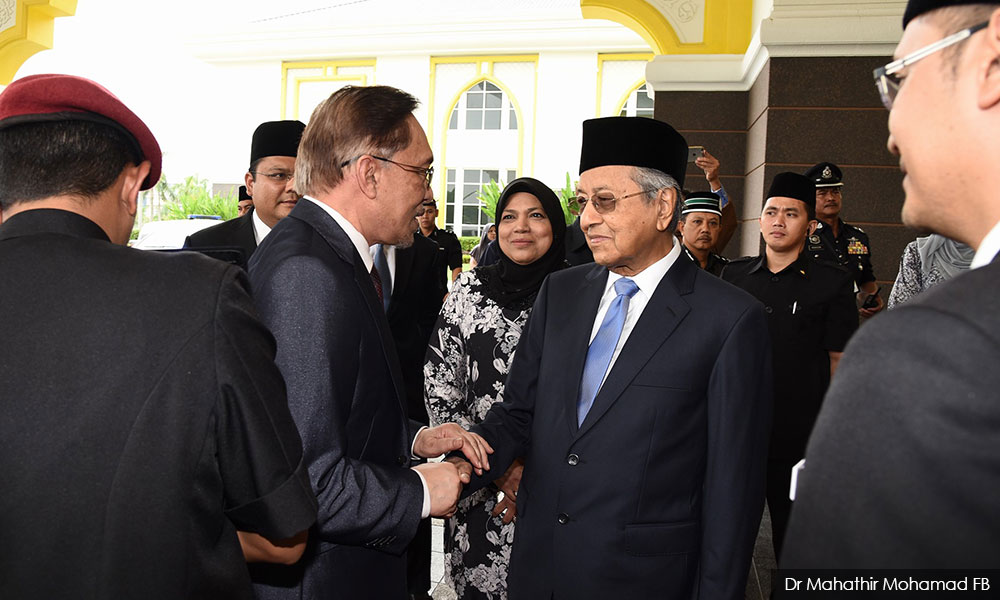

After GE14, when Anwar was finally pardoned on May 16, 2018, the question of forgiveness resurfaced. Anwar had by then grown immune to the question of forgiving Mahathir, to the extent that he would soliloquise by doing the Q&A himself:

"In fact, one of the very well-known statesmen in the world was joking with me, ‘Anwar, are you sure? Are you telling me the truth? Come on, look at me and say that you’ve forgiven him [Mahathir].’

"So I looked at him, I said, ‘My interest now is the wealth of the nation. I have forgiven him, and he has proven his mettle, he has made sacrifices […].’ He has now supported the reform agenda, he has facilitated even my release. Why should I harbour any malice towards him?”

Recalling Anwar’s ambiguity in 2016, this 2018 statement stands firmer. But a pretext remains if one reads with greater prudence.

Preceding the reconciliatory clause “I have forgiven him”, is “My interest now is the wealth of the nation”. This urgency of the “now” is a conditional “only-if” statement, resembling the pretext in his 2016 statement aforementioned: “I have forgiven a lot of people, a lot of things, but my concern is the present”.

What lies beneath

Nonetheless, Anwar’s response appears to have finally allayed the desperation. His pretext, his conditional forgiveness, are too clumsy for journalism. After the press conference, Bloomberg took the liberty to condense his speech into a proper finality (“I have forgiven him”), while Bernama also formulated an easily digestible headline ("I have forgiven him – Anwar Ibrahim").

But to what extent are these a fair conclusion? For never has Anwar answered directly to the question of forgiveness, without first emphasising his priority and his interest in the “now”. It is, to recall Derrida, only “politically necessary” for Anwar to forgive Mahathir.

What lies underneath this political forgiveness is an elided threshold, an abyss filled with the questionable and the unanswerable, which have never been spoken of.

To recall them: What is the condition of holding a former minister accountable for his previous liabilities while ignoring another? How do we account for the unspeakable threshold, where liabilities pass into forgiveness?

“Forgiveness” has become the veneer to the unspeakable threshold in Malaysian politics. It is political indifference disguised as sympathetic generosity. It is a refusal to acknowledge history disguised as a commitment for the greater good.

Political amnesia might be too strong a word for this phenomenon. Neither should we explain this predicament with an oversimplifying “forgive and forget” or “forgive but not forget”.

The crux of the problematic lies in the collective withdrawal from engaging with the unspeakable threshold. Unanswerable questions, that which oblige one to respond without an answer, are generally detested as unconstructive criticism.

With the recent hagiography of Mahathir, not to mention the subsequent euphoria over his pair of Bata sandals or his multivitamin supplement Berocca, almost everything he touches becomes a viral hit.

The winds of change have garnered Mahathir renewed sympathy. Forgiving Mahathir has become politically necessary, if not the only way forward.

This sense of optimism is rare in Malaysia, but it should be equalled with a parallel effort to discuss his previous liabilities, which have never seen the light of day.

This should be done not to uphold a “verdict”, but to acknowledge the unspeakable, and to detail and understand how Najib could have done what he did within an impenetrable system of power first instituted and championed by Mahathir.

TAN ZI HAO is a postgraduate student in the Department of Southeast Asian Studies, National University of Singapore. He is also a conceptual artist whose artworks can be viewed at www.tanzihao.net. As both artist and writer, he is interested in the arts, language, cultural politics, and mobilities. -Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.