Ah Hock did not plan to be a “business owner”. He planned to live a simple life.

When his uncle fell ill, the family shop in Sungai Buloh had no one else to keep it running. A small hardware and building materials shop, the sort that sells cement, pipes, wiring, paint and the little items people only notice when something breaks.

Ah Hock stepped in, first to help for a few months, then stayed because the bills did not stop just because the old man could not stand behind the counter anymore.

He is in his mid-40s now. His life is not complicated. Work, family, payroll and suppliers. Make enough to keep the shop open, pay the rent, pay staff on time and put aside whatever he can for two children who have grown up too fast.

His son made it into a public university after STPM, but his daughter did not. That is the household reality behind every policy debate. One path is affordable. The other path is expensive but urgent. Private college fees do not wait for policy stability.

That is why, when the government talks about “helping SMEs”, Ah Hock listens carefully. Not because he expects miracles but because he is living the thin margin between coping and collapse.

And lately, what he hears is a government that keeps changing the rules mid-game.

High turnover does not mean big business

Ah Hock’s shop has a turnover that can look impressive to outsiders. Building materials are expensive. One contractor’s order can run into tens of thousands. A few big deliveries and suddenly annual sales cross RM1 million.

But turnover is not profit. His business is high volume, low margin. Customers ask for credit. Suppliers want payment yesterday. If a refund is delayed or costs spike unexpectedly, the cash flow pain is immediate. The staff do not accept “policy transition” as an excuse for late salaries.

e-Invoice and the moving goalposts

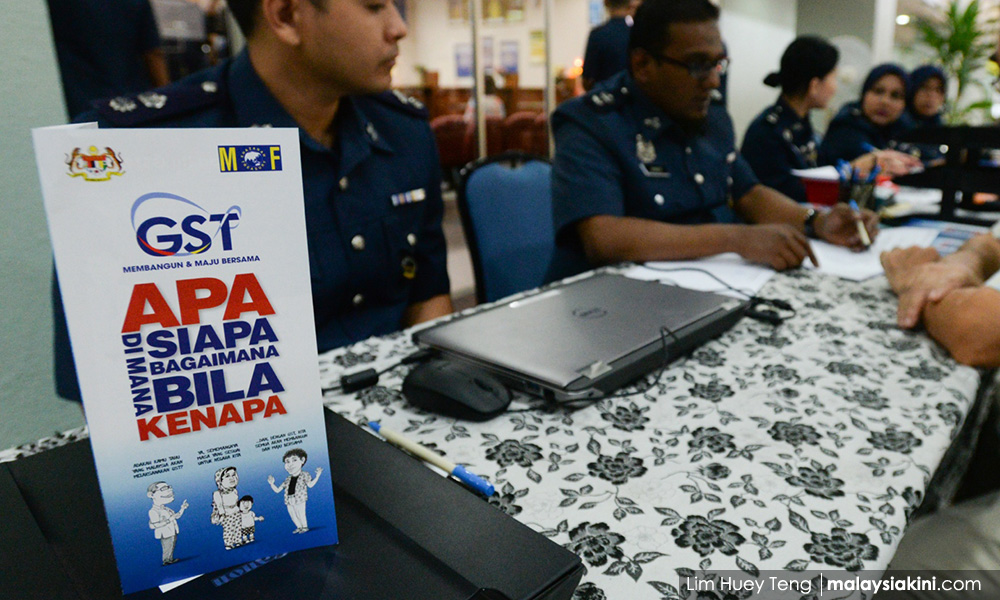

Ah Hock remembers the goods and services tax (GST) days. Many Malaysians disliked GST, and he understands why. It hit everyone visibly, but from a business perspective, there was one part that at least made sense: input tax credits.

If he paid tax on inputs, there was a structured way to reclaim it so that he didn’t have to pass on the cost to his customers. The system was more transparent, more trackable and easier to plan around.

Today, what he experiences is different. It is uncertainty.

e-Invoice is the best example. He is not against digital compliance. He already uses banking apps and basic accounting software. The problem is the way the implementation kept shifting during 2025, not just in dates but in who is even covered.

In June 2025, the Inland Revenue Board (IRB) updated its guidance and raised the exemption threshold from RM150,000 to RM500,000, alongside timetable adjustments.

In December 2025, the threshold was raised again, from RM500,000 to RM1 million for 2026, a clear sign that readiness was still a problem.

Then on Jan 5, enforcement for businesses with RM1 million to RM5 million turnover was deferred again, pushing it to 2027 with a penalty-free transition period.

Ah Hock reads this and thinks of the money he already spent because he did what people told SMEs to do, which is comply early, prepare early, and avoid trouble later. He upgraded systems, paid for integration and trained staff.

Now, the “early” becomes “too early”. This is the part policymakers miss. Every deferment creates a new injustice: it shifts the burden onto the early movers who acted in good faith. It trains the market to delay compliance, and it punishes the few who try to be responsible.

Expand SST first, explain later

At the same time, when Ah Hock was dealing with implementing e-Invoice, sales and services tax (SST) expansion came in the middle of 2025. It entered the shop through rent, suppliers and customer behaviour.

Rental and leasing services were taxed at eight percent. That matters because Ah Hock does not own his shop lot, and rent is not something he can optimise away. It is a fixed cost that keeps the lights on.

Then, on Jan 5, the prime minister announced that the service tax on rental and leasing is reduced from eight to six percent, and raised the SME exemption threshold from RM1 million to RM1.5 million, with a one-year exemption for newly registered SMEs.

Again, he is not angry that the rate came down. He is angry that it went up abruptly without proper calibration and then needed a quick correction. For SMEs, it is not the final rate that hurts most. It is the stop-start planning. He cannot price goods properly when cost inputs keep changing.

He cannot promise stable overtime to his drivers when projects get postponed. He cannot explain to customers why today’s quotation is different from last month’s without sounding like he is making excuses.

That feels like firefighting. If the policy needs repeated extensions to prevent real-world disruption, it suggests the original rollout was rushed.

Why celebrate getting your own money back

And then there is the tax refund issue, the one Ah Hock finds hardest to swallow.

The IRB reported that refunds processed and completed in 2025 amounted to RM22.5 billion involving 3,713,025 cases, following the injection of additional funding late in the year.

The government frames this as performance. Ah Hock hears it differently. A refund is not a bonus. It is his money, overpaid. When it comes back late, it is not generosity; it is a delayed repayment.

In practice, delayed refunds mean he needs to scramble to make ends meet. He still has to pay wages, EPF, Socso and suppliers on time. His children’s education bills do not pause because a refund is pending. His staff do not accept “processing timelines” as a reason for late salaries.

A new normal for businesses

This is what the business environment feels like to Ah Hock. A compliance system that keeps changing thresholds and dates. A tax expansion that hits costs like rent, then gets revised. Exemptions are extended after the disruption is already felt. Refund headlines that sound impressive but gloss over the cashflow pain of delayed repayments.

The consequences are not abstract. They land on his staff, who face uncertain overtime and fewer increments. They land on his customers, who pay a little more each month as costs creep through the supply chain. They land on his family, where one child in public university is a relief, and the other child’s private college fees are a looming weight.

If SMEs are to comply and grow, the minimum requirement is policy stability. Publish a timetable that does not shift every quarter. Stop raising thresholds as a substitute for proper preparation. Offer transitional support that does not punish early adopters. Set clear service standards for tax refunds because cash flow is survival for SMEs.

Ah Hock does not ask for special treatment. He asks for rules that stay put long enough for an honest small business to plan, pay staff and keep two children’s future from slipping away. - Mkini

WOON KING CHAI is the director of the Institute of Strategic Analysis and Policy Research.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.