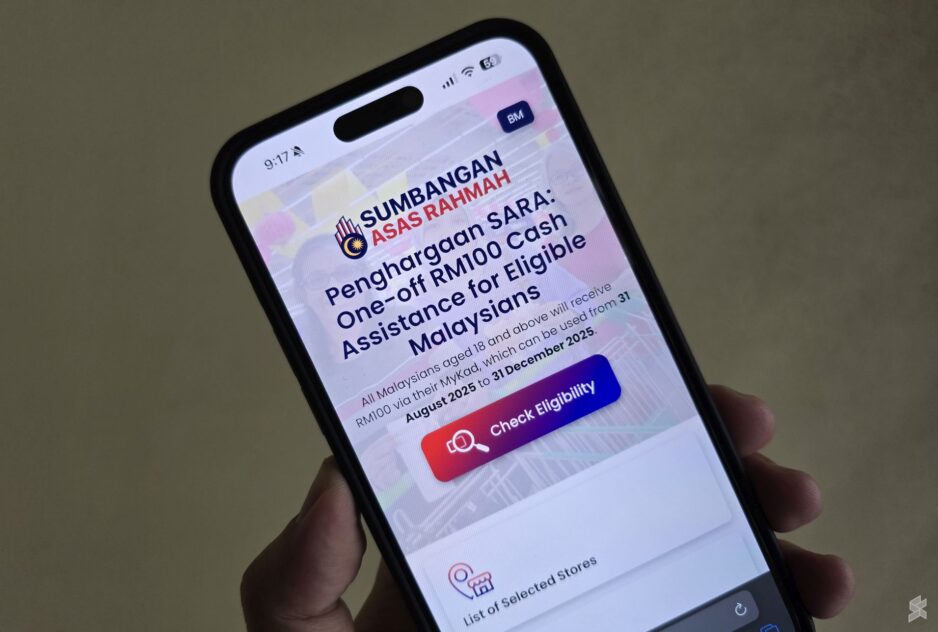

WHEN Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim tabled Budget 2026, one of the most widely discussed measures was the government’s decision to once again provide a RM100 cash payment to every Malaysian adult aged 18 and above under the Sumbangan Asas Rahmah (SARA) and Sumbangan Tunai Rahmah (STR) programmes.

According to the Finance Ministry, the payment will reach roughly 22 million adults, functioning as a short-term cushion for households facing cost-of-living pressures ahead of festive seasons.

The measure is unequivocally popular. In an economic environment characterised by inflationary stress and stagnant salaries, even a little transfer might alleviate the burden of everyday necessities. The action is politically inclusive and administratively uncomplicated, where everyone is eligible, and everyone gains advantages.

However, underneath its superficial allure exists a more profound policy question: is this simply a transaction, or can it evolve into a component of a wider revolution in Malaysia’s support for its citizens?

There is no doubt that many Malaysians will welcome the cash. The previous round of SARA assistance saw a large majority of recipients spend the money within days, a sign of genuine need and the immediacy of economic stress.

The government’s total commitment of around RM15 bil to cash aid in 2026 demonstrates an earnest desire to help. But one-off handouts, however well-intentioned, are not a substitute for building lasting financial capability.

A fixed RM100 payment offers temporary relief for a few days’ expenses, but it fails to significantly bolster future resilience. Instead, it jeopardises the perpetuation of a dependency cycle because individuals rely on Putrajaya for temporary relief instead of avenues to enhanced earning potential.

The universality of the payment, albeit politically attractive, undermines its economic specificity: high-income beneficiaries obtain the same amount as low-income individuals, diminishing the potential effect on those that require assistance the most. Over time, this extensive distribution may become financially burdensome yet socially superficial.

Cash transfers need not be abandoned, but they can be reimagined. Instead of treating them purely as consumption boosters, the state could use such programmes to signal a parallel commitment to capability building.

A portion of future aid could be linked to optional redemption for short-term courses, vocational certifications, or entrepreneurship toolkits, enabling recipients to convert temporary assistance into skills and employability.

Basic behavioural nudges may enhance efficacy. In addition to disbursement notifications, beneficiaries could receive links to budgeting tools, micro-investment opportunities, or details regarding upskilling programs provided by MDEC, HRD Corp, or community colleges.

These inexpensive linkages would transform aid from a simple disbursement into a catalyst for engagement in the formal sector.

More importantly, the government could measure not only distribution efficiency but also impact on how recipients spend, whether short-term consumption translates into improved welfare, and whether complementary support mechanisms reach those who need them most.

Transparency in outcomes would allow future budgets to refine targeting without politicising assistance.

Critics may dismiss monetary assistance as a populist policy; yet, such a judgement is unfair when families are in distress. The fundamental issue is not a lack of compassion; rather, it is the absence of a mechanism that links alleviation to advancement.

In a nation where wealth disparities endure and youth unemployment remains persistently high, fiscal instruments must be crafted to empower rather than simply placate.

Budget 2026 rightly places people at the centre of economic recovery. The RM100 gesture is a nod to inclusivity and empathy. Yet for Malaysia to move from safety nets to springboards, future budgets must increasingly blend short-term assistance with long-term empowerment.

Helping citizens cope with today’s prices is essential but helping them command tomorrow’s income is transformative.

The 2026 cash aid measure is understandable and politically defensible. It reaches everyone, it arrives fast, and it signals that the government is listening. But it also exposes a missed opportunity to pivot from relief to resilience.

The difference between a transfer and a transformation lies in what follows the payment: whether it becomes a brief respite or the foundation of a stronger, more skilled society.

Malaysia has proven adept at distributing money efficiently. The next challenge is to distribute opportunity with the same zeal. Only then can the promise of shared prosperity move beyond the wallet, and into the fabric of everyday capability.

Galvin Lee Kuan Sian is a PhD Researcher in Marketing at the Asia-Europe Institute, Universiti Malaya and serves as a lecturer and Programme Coordinator in Business at a private college in Malaysia.

The views expressed are solely of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of MMKtT.

- Focus Malaysia.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.