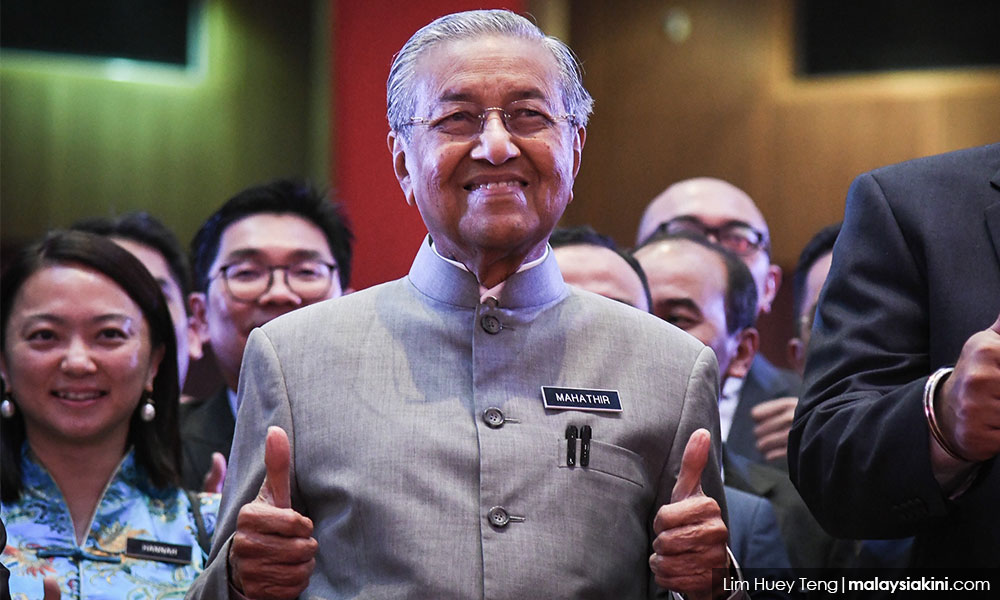

Pakatan Harapan’s unexpected victory on May 9, 2018 was one of monumental proportions as the ruling BN, under Umno’s control, had instituted a series of unscrupulous methods to retain power. Harapan, led by Mahathir Mohamad, had achieved a colossal feat, unseating a mighty Umno that had never lost power.

Inevitably, in the euphoria over this unanticipated and unprecedented regime change, much was expected of Harapan, including the dismantling of unjust laws, reforming of public institutions and promulgating of inclusive policies. However, even then, analysts had cautioned Malaysians not to expect too much too soon as the process of instituting real change after long-term unbroken authoritarian rule would both be tedious and time-consuming.

Change without change

However, in one specific area, where much change was expected and could have been quickly instituted, little has changed, even after a public debate transpired about this topic.

Harapan had pledged to reform a well-entrenched government-business institutional framework that had contributed to development as well as extensive corruption, debilitating patronage, even a kleptocracy. Umno’s fall was largely attributed to the abuse of 1MDB, Felda and Tabung Haji, institutions known as government-linked companies (GLCs), raising expectations of reform of this government-business nexus. However, what appears to be hampering GLC reform, in spite of a public debate about their role in the economy, is the matter of consolidating power which is contributing to the perpetuation of the politics of patronage.

For this reason, too, a communal perspective to policy implementation, in keeping with Umno’s longstanding affirmative action-based redistributive agenda to transfer corporate equity to bumiputeras, remains very much another contentious policy debate.

When Minister of Economic Affairs (MEA) and deputy president of PKR, Azmin Ali, recently announced that a bumiputera policy was imperative, one reaction was particularly noteworthy. Anwar Ibrahim, prime minister-in-waiting and PKR president, contradicted Azmin by saying “that’s his personal opinion”, and then added that the “Pakatan Harapan manifesto does not sideline Malays and bumiputera, but calls for a transparent and non-racial approach, with an agenda to help the poor and the alienated”.

This GLC framework and its employment to institute the bumiputera policy had come to be entrenched in the economy as well as the political system during Mahathir’s 22-year reign, from 1981 to 2003, as prime minister. Another key figure who shaped how this government-business nexus evolved while he served as Mahathir’s finance minister was Daim Zainuddin (1984-1990), now his economic advisor. By May 2018, this GLC structure had become so huge – and so abused by Umno – that Mahathir himself described it as a “monster”.

Although Harapan had promised a new approach to governing Malaysia, events since May 2018 suggest a worrying degree of continuity, precipitating conflicts within the coalition. Rather than give up an appealingly effective lever for consolidating power, some Harapan leaders appear inclined to borrow the same tools and strategies employed by Umno.

Shuffling GLCs

Soon after Harapan formed the government, a disturbing series of events occurred. Mahathir immediately inaugurated the MEA, under Azmin’s charge. Even before GE14, reports emerged of intense factionalism in PKR, due to differences between Anwar and Azmin. Meanwhile, Mahathir is widely thought to be uncomfortable about transferring power to Anwar, whom he had removed from public office in 1998. One persistent prickly topic is that Mahathir has not announced a specific date on which Anwar will take office as prime minister.

Instead, what occurred was that the newly-minted MEA took control of numerous GLCs from the Ministry of Finance (MOF), under the jurisdiction of the DAP’s Lim Guan Eng. Meanwhile, Malaysia’s only sovereign wealth fund, Khazanah Nasional, was channelled from MOF to the Prime Minister’s Department, under Mahathir’s control.

The government did not explain the need for this discreet shuffling of GLCs between ministries, even when queried about it. And why MOF’s enormous influence over the corporate sector had to be so significantly diminished was also not explained. What is important to remember is that, under BN, the prime minister had also functioned as the finance minister, a practice introduced by Mahathir in 2001. Harapan, while in opposition, had pledged that the same politician would not hold both portfolios.

Next, in September 2018, Azmin’s ministry convened a Congress on the Future of Bumiputeras & the Nation. Mahathir stressed at this congress the need to reinstitute the practice of selective patronage, targeting bumiputeras, a plan endorsed by his economic advisor, Daim. Subsequently, numerous ministers began actively calling for the divestment of GLCs, a subject also in the 2019 budget.

Then, when Khazanah began reducing its equity holdings, including in Malaysia’s second largest bank, CIMB, these divestments raised the question of whether this marked the commencement of a transfer of control of key enterprises to well-connected business people, even proxies of politicians, a common practice by Umno in the 1990s. In ensuing debates about these divestments, the question was raised whether the sale of GLCs was an attempt to create an influential economic elite, even oligarchs, who could check politicians in power in the event of a leadership change.

Then, another contentious issue occurred. Minister of Rural and Regional Development, Rina Harun (below), of Mahathir’s Bersatu, appointed politicians from her party to the boards of directors of GLCs under her control. Under Umno, this ministry, which has an enormous presence in states with a bumiputera-majority population, had persistently been embroiled in allegations of corruption, undermining its activities to redress regional inequalities and reduce poverty.

So important is this ministry, in terms of mobilising electoral support, that it was always placed under the control of a senior Umno leader. The minister’s directorial appointments suggested a worrying trend of the continuity of irresponsible patronage-based practices of the old regime.

In December 2018, Bersatu leaders openly declared their intent to persist with the practice of selectively-targeted patronage. At its first convention after securing power, the declaration by its president, Muhyiddin Yassin, that “Bersatu should not be apologetic to champion the Bumiputera Agenda” was enthusiastically supported by members, suggesting an element of opportunism in the party. These trends implied that Bersatu’s key concern was its immediate need to consolidate power and muster support, not institute appropriate long-term socioeconomic reforms.

Elite domination

All told, then, these specific, sometimes discreet, steps since GE14, to re-introduce the bumiputera policy as well as the reluctance to review how GLCs function, call into question Harapan’s pledges to institute real change.

Moreover, under Harapan, by its own admission, the volume of government intervention in the economy will still be substantial. Worryingly, what is absent is a coherently-structured industrial plan to cultivate entrepreneurial private firms through a transparent and coherent form of government intervention. There is no roadmap to get GLCs to target specific core industries requiring heavy capital investments and extensive research and development funding to rapidly industrialise the economy.

This state of play raises an important question about an interesting phenomenon: what happens, in terms of dismantling rent-seeking and patronage and instituting reforms to curb corruption, when a new regime of politicians sees this framework as a mechanism to consolidate power?

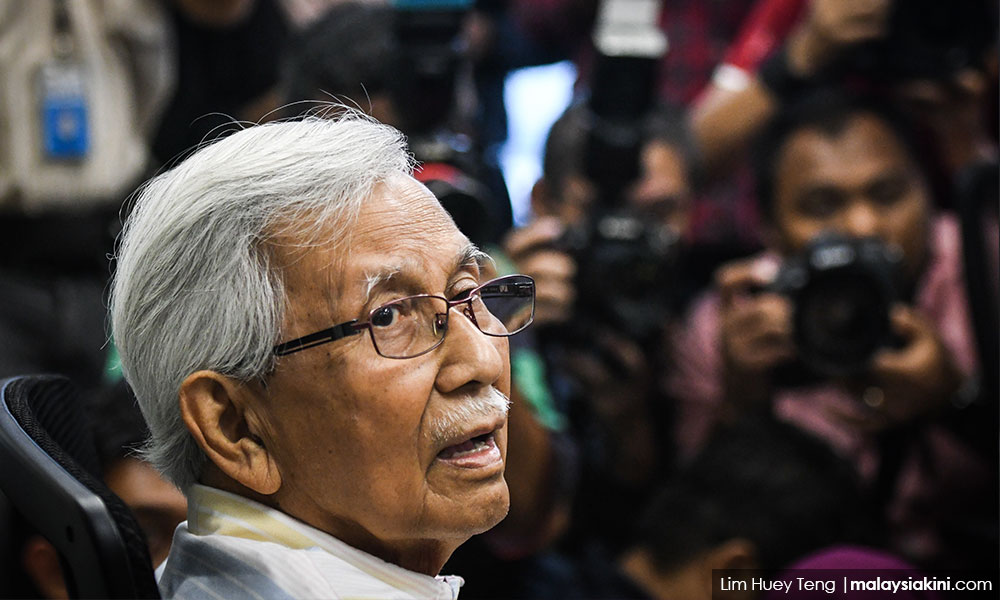

A link between two core issues remains in place after regime change: elite domination and the continued use of selective patronage, legitimised by race-based policies that are to be implemented through GLCs. Under Umno, elite domination was obvious, with Barisan component members subservient to then-prime minister Najib Razak. In Harapan, Mahathir and Daim (below) appear to have enormous influence when it comes to decision-making on core issues, though the parameters of their power remain unclear.

What is equally troubling is that GLCs remain an opaque form of government intervention in the economy. And, since there is little public knowledge of GLCs, it is the lack of transparency of these enterprises that can allow for their continued abuse by politicians.

Fragile state

Since Harapan is a coalition of disparate parties led by politicians who coalesced only because of their common agenda – Najib’s removal from power – what prevails now can be described as a “fragile state”.

This fragility is also because of the uneasy relationship between Mahathir, who leads the second smallest party in Harapan, and his long-time nemesis-now-political-ally Anwar, who leads the party with the highest number of parliamentary seats. Meanwhile, there appears to be no resolution to PKR’s acute factionalism, apart from an uneasy truce between Anwar and Azmin, who apparently is closely associated with Mahathir.

What is emerging is new forms of power relations through the unhealthy circulation of political elites from the old regime into Harapan, as well as alliances between leaders from different parties in this coalition. Umno parliamentarians are lining up to join Bersatu, a quick route back to power for them after their unexpected ouster. By co-opting them, Mahathir’s small party can swiftly fortify its extremely weak base in bumiputera-dominant states.

But Bersatu’s cooptation of discredited Umno members is gravely undermining support for Harapan, as well as Mahathir’s credibility. There was even talk of a no-confidence motion against Mahathir as prime minister in parliament in March 2019, which fortunately did not occur as it would have undermined economic confidence in this government. This complex situation of political infighting is raising fears that politicians in power may move to create, through the divestment of GLCs, powerful business elites, even oligarchs, to check other political elites.

Since a structural framework that allowed politicians to exploit institutions in various ways to serve vested political and economic interests remains in place, one year on, a disturbing new question has emerged. What are the possible political and economic outcomes in this situation in which contending elites in Harapan struggle to consolidate their respective power bases?

Political economic outcomes can involve protecting the property rights – through ongoing and much-needed institutional reforms – of business elites who acquire privatised GLCs, thereby preventing expropriation of these companies by the government in the event of a leadership change. Political outcomes can also entail endorsing entitlements that give one large segment of society privileged access to government-generated concessions.

Inevitably, a related issue is the necessity of targeted race-based policies that can serve as a mechanism to retain patronage-based networks and consolidate power bases, which is particularly important for Bersatu. This approach can stymie domestic investments by non-bumiputeras, which was a persistent problem during Umno’s rule.

Ironically, it was these unproductive government-business networks that Harapan had promised to dismantle to forge a “New Malaysia”. This New Malaysia was to be devoid of race-based political discourses and policies, with the GLCs deployed to promote equitable development and redress social inequities. These pledges have not been instituted.

On the first anniversary of Harapan’s overthrow of Umno, consolidating power appears to be more important for Malaysia’s new political elites than restructuring the economy.

TERENCE GOMEZ is professor of political economy at the Faculty of Economics & Administration, Universiti Malaya. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.