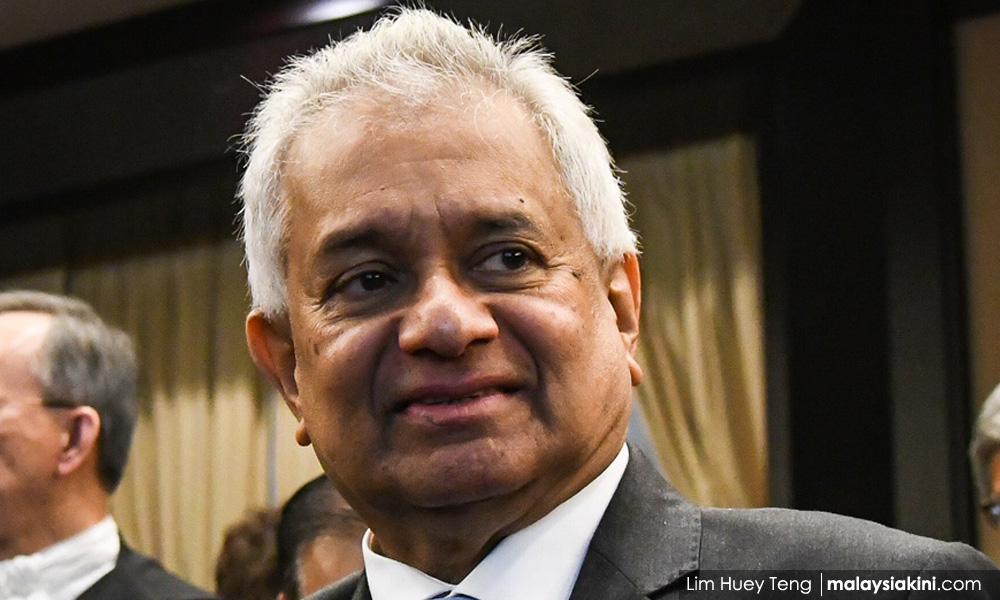

The reasons given by Attorney-General Tommy Thomas in his media release explaining the revocation of the service of lawyer Syazlin Mansor from representing the Housing and Local Government Ministry and the Fire Services Department in the inquest into the death of fireman Muhammad Adib Mohd Kassim, raise more doubts and questions than answers.

This is especially since it was done in a high handed manner, 36 days after Syazlin had been involved in the inquest without objection by the Attorney-General’s Chambers and the objection only came after she called the senior forensic pathology consultant Prof Shahrom Abd Wahid as expert witness who testified that scientific evidence pointed to the conclusion that Adib was indeed murdered during the Seafield temple riot.

The interest of all parties in an inquest is to find the truth. An inquest is not a criminal trial, for there is no prosecution and there is no defence; likewise, there will be no winning or losing party at the end of the proceedings. Therefore, the claim made by Thomas that Syazlin was in a position of conflict of interest if she were to continue representing all three parties, namely the ministry, the Fire Department and the family of Adib because “the interests of these parties may conflict” is clearly misguided and bears no basis under the law.

While the source of power to establish an inquest is derived from section 339 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CPC), the procedures governing the proceeding are spelt out in the Practice Direction No. 2 of the Judiciary dated April 8, 2014. There, paragraph B of Enclosure A thereof clearly states that “there are no ‘parties’ to an inquest;” while paragraph E stresses the “inquisitorial” nature of an inquest, and not adversarial. In fact, our Court of Appeal in the case of Teoh Meng Kee v Public Prosecutor [2014] 5 MLJ, summed up the role of those involved in the proceeding as merely to assist the Coroner's Court in a fact-finding mission, and nothing else.

Save for the coroner at the end of the proceedings, it is not for any of those involved in the fact-finding mission to take any position concerning the facts of the case. Therefore, the complaint raised by Thomas that “Syazlin took an active part in the inquest, often contradicting the positions (the Attorney-General’s Chamber’s) DPPs have taken, thus causing embarrassment in her capacity as the ministry’s lawyer” is simply untenable, for the DPPs should not, in the first place, prematurely take any position with regard to the cause of death, be that by accident or homicide, before the proceeding ends.

If the DPPs have already taken a position as to what caused the death of Adib, there would be no reason to proceed with the inquest, since the very reason that an inquest is called is that the cause of death is unknown. Therefore, whatever theories there are concerning the cause of death must be allowed to be presented in full in the course of the proceedings, and it is highly unbecoming for the AG to fault Syazlin’s active role in questioning the witnesses to test the veracity and falsity of their testimonies. Such an active role should instead be commended because that is exactly what is expected of every advocate and solicitor and every officer of the court – to uphold the cause of justice without fear or favour.

But all these, and the rule of law would only have meaning if the AG and his office have an open mind instead of being all too hasty. It is even more worrying that we have an AG that cannot discern the difference between a fact-finding mission on the one hand, with that of a trial on the other. - FMT

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.