Mental health issues in Malaysia seem to be worsening, going by reported figures.

By now, most of us would have come across at least one news report citing the glaring "one in three" statistic taken from the 2015 National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS).

The population survey, conducted by the Institute for Public Health, found that a mind-boggling 29.2 percent of Malaysians aged 16 and above are living with some form of mental health issue.

This is a marked rise from the 11.2 percent affected by mental health issues found in the 2006 NHMS.

Piecing together these statistics, a sobering picture emerges. Over the course of a mere decade, a drastic threefold rise in mental health issues appears to have befallen the population – a phenomenon tantamount to a significant public health concern.

In light of the apparent escalation, certain leaders have spoken up to voice their concern.

Last October, at the launch of World Mental Health Day, Women, Community and Family Development Minister Dr Wan Azizah Wan Ismail called for a review of the national mental health policy, "based on the growing trend of mental health issues".

Speaking at the same event, Health Minister Dzulkefly Ahmad pledged that his ministry would continue to expand efforts to promote better mental health, and urged NGOs and local community leaders to work together to increase awareness.

Such sentiments – coming from the leaders of two ministries which arguably hold the greatest sway over influencing mental health outcomes within the population – are certainly welcome. If anything, speaking openly about mental health issues can make a difference in improving perceptions and reducing stigma.

A growing trend?

Yet, all things considered, are mental health problems truly "a growing trend" amongst Malaysians?

To have a more holistic view, we should step back from merely looking at the "snapshot" of population mental health issues in 2006-2015, and consider patterns of change over a longer period.

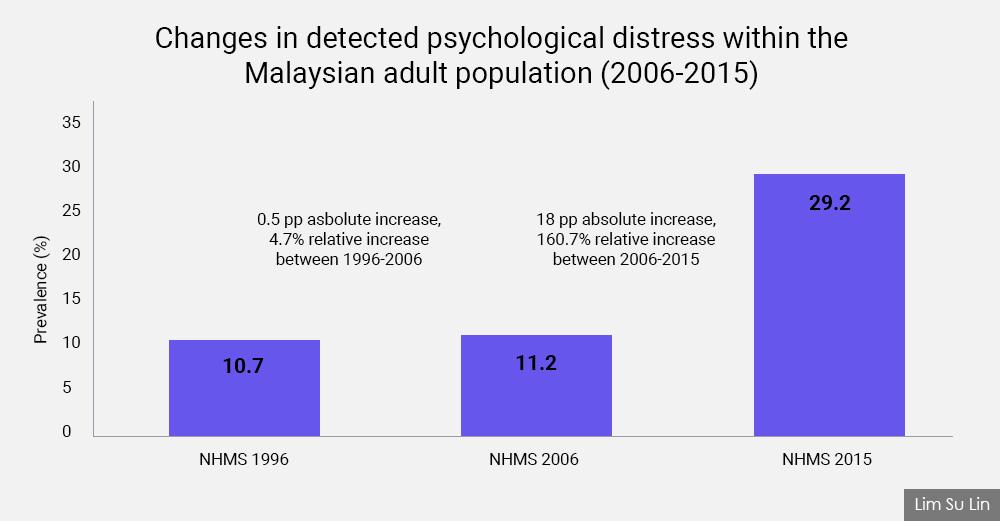

The above figure depicts changes in the prevalence rates of detected psychological distress among adults over a period of 20 years, based on NHMS reports published in 2015, 2006 and 1996.

At immediate glance, there is a visibly stark difference between the detected prevalence of mental health problems from 2006 to 2015, versus the 10 preceding years.

Between 1996 and 2006, the prevalence of mental health problems rose from 10.7 percent to 11.2 percent, a 4.7 percent increase in relative terms.

This increase seems reasonable when we consider the spread of globalisation and the fast-paced social and technological transformations taking place during this period.

Put into context, these tandem changes would surely have impacted families and society, not just economically, but also in terms of their mental health and wellbeing.

By contrast, however, the tremendous spike in prevalence rates seen from 2006 to 2015 is much harder to explain. Figures escalated from 11.2 percent to 29.2 percent, rising by 18 percentage points. In 2015, detected mental health problems had increased 160.7 percent relative to 2006.

At face value, this is nothing short of a stunning surge. It seems to show that the state of mental health in the country became drastically worse in the latter period, despite both time intervals being more or less similar.

Different measures

But before we prematurely declare an epidemic of mental illness, it is important to understand how these figures were derived.

In 1996, 2006 and 2015, NHMS used a self-reporting measure known as the general health questionnaire, or GHQ, to measure mental health outcomes in the adult population (different screening measures were used for the 2011 and 2012 cycles).

In simple terms, GHQ is a psychiatric screening tool which detects non-specific psychological distress in a person or population. It uses a scale with validated cutoff points to identify cases of non-specific 'common mental health disorders'.

While the original version of the GHQ consisted of 60 'items' or questions, shorter formsare also available, each comprising 30, 28 and 12 questions.

A critical point – which is often missing from news reports – is the fact that different versions of the GHQ have been used in the NHMS reports to screen and detect mental health problems over time.

In 1996, the authors of NHMS applied the abbreviated 12-item version (GHQ-12). This was then switched to the longer 28-item version (GHQ-28) in 2006, before returning again to GHQ-12 in 2015.

Though no explanation for the variation in usage of screening tools is given in these reports, the 2015 NHMS does contain a citation from a 1997 validity study, describing GHQ-12 as “robust and work(ing) equally well as the longer instrument(s) as a screening instrument for case detection... Its brevity makes it attractive for use in busy clinical settings as well as for large-scale epidemiological settings."

Based on this, the choice to use the shorter-item version of the GHQ might have been for practical purposes, to address challenges of time and resources faced in population-level public health research.

Both GHQ-12 and GHQ-28 have been used in a range of demographically and culturally varied population settings worldwide to assess and detect mental health problems.

Moreover, scientific assessments have shown that both tests have comparably strong psychometric properties (referring to the reliability or internal consistency of an instrument, and the accuracy of its test results).

In that sense, since GHQ-12 and GHQ-28 are both validated, accurate and dependable measures, it is not necessarily wrong to have used both versions to screen for mental health.

However, the non-homogeneity does make it difficult to evaluate long-term changes in population mental health over time accurately.

'Threefold increase'?

This leads to the main point: the oft-quoted “threefold increase in mental health issues” between 2006 and 2015 is a somewhat misguided statistic, once we understand that different versions of the screening tool were used to detect mental health problems in each of these years (GHQ-28 in 2006, and GHQ-12 in 2015).

Another caveat to bear in mind when reading mental health data from NHMS is that these reports measure prevalence rates – meaning the total number of cases of mental health problems, including both old and new cases, occurring within a period of time.

Hence, another clue as to why population mental health problems appear to be increasing in NHMS reports could lie in increasing population life expectancy.

As more people continue to live longer, the number of pre-existing cases of mental illness over a given time period will also logically increase. Therefore, the rise in prevalence rates does not necessarily mean that we are seeing increasing numbers of new cases – only an extension in the 'lifespans' of people living with mental health problems.

Returning to the main question: have mental health issues truly worsened in Malaysia?

Instead of taking NHMS evidence as the gospel truth, our government should make an effort to measure mental health outcomes as precisely as possible in other ways.

Aside from population research, information from various medical sources such as hospital records, patients’ health history, prescription information from psychiatrists, and case records of mental health referrals to community clinics represent important indicators that tell us about the state of mental health in the country.

In this age of big data analytics, analysts and policy researchers working on mental health issues, whether in government ministries, think tanks or other entities, need to break out of their silos.

By working together to gather, share and piece together the data, they can help form a better, more accurate overall picture of how mental health outcomes have changed over the years.

This information should then be transmitted to decision-makers in government, to help them make better-informed policy responses to address mental health issues.

Lastly, taking the NHMS results as separate, standalone figures, the 29.2 percent prevalence figure in 2015 is still very significant, compared to earlier prevalence rates of mental distress seen in earlier years.

At the end of the day, while mental health issues may not necessarily be growing, it is quite possible that Malaysians have started to take a more open approach towards mental health issues over the years.

Compared to previous generations, more people nowadays may be more willing to open up about their mental health struggles. If this is true, it represents a silver lining in the otherwise current cloudy national conversation.

Whether increasing or decreasing, mental health, like any other health concern, is worth paying attention to.

If an attitude of greater acceptance in our society helps reduce stigma, and increases the chances of those whose lives have been affected by mental illness to seek the treatment and care that they need, then surely this should be regarded as a positive development to be nurtured and encouraged.

LIM SU LIN is a policy analyst with the Penang Institute. A History graduate from Cambridge University, her research interests lie primarily in promoting good mental health as a criterion for public policy, and to carry out research into the social, economic and cultural factors that help to enhance mental well-being and support recovery from mental distress. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.