As the Mahathir Mohamad administration prepares to celebrate the first anniversary of its audacious election victory, a controversy over a savings fund for Muslim pilgrims provides a sobering reminder that the perennial issue of race relations is still the most daunting challenge facing the “new Malaysia”.

A rescue plan the Pakatan Harapan coalition devised last December to revive the struggling balance sheet of Lembaga Tabung Haji was meant to be anything but controversial.

Soon after taking power, Mahathir’s administration uncovered that the fund – tasked with helping Muslims save for a pilgrimage to Mecca – was knee deep in trouble.

Its liabilities outstripped its assets, making it untenable for the fund to pay good dividends to finance haj journeys. The government’s solution was simple.

The finance ministry, led by Lim Guan Eng, formed a special-purpose vehicle that took over some 19.9 billion ringgit (US$4.59 billion) of the fund’s underperforming assets. This would allow the fund to balance its books and pay out dividends.

Little did Lim and others in the nascent administration expect that their opponents – defeated in the May 9 election – would turn the innocuous rescue plan into a racial issue.

It was a bewildering accusation – one with racial undertones suggesting Lim, an ethnic Chinese, had intentionally set up the special-purpose vehicle to raid funds saved by poor Malays to perform the haj. Lim immediately shot back that the issue was under the purview of the Islamic Affairs Minister, Mujahid Yusof Rawa.

It was “malicious” to accuse him of “robbing” Tabung Haji, the minister countered, but for Tajuddin the job was done. He had successfully seeded the false perception that Lim’s finance ministry had an ulterior motive in buying out the troubled Tabung Haji assets.

As euphoria fades over the birth of a

“new Malaysia” following Pakatan Harapan’s election victory, administration insiders say these are exactly the kind of racially charged political confrontations they worry most about. Asked by This Week in Asia what they thought posed the biggest risk to the stability of their government, lawmakers, ministers, and political aides almost unanimously spoke about race.

Concerns about ethnic relations and the preservation of Malay rights came second to worries about the economy in a recent survey by the Merdeka Centre think tank on key issues voters cared about.

The same survey showed support for the government had slipped to 39 per cent from 79 per cent last May. Umno, for a while seeming to be on the brink of collapse, is showing signs of revival.

Since forging a post-general-election alliance with hardline Islamist party PAS (Pan-Malaysian Islamic Party), it has won three back-to-back by-elections.

In contrast, the Pakatan Harapan government has been fighting fires on multiple fronts. Weak economic data has softened investor confidence, and Mahathir is mired in yet another personal battle with the country’s powerful constitutional monarchs. But the starkest challenge lies in keeping race tensions at bay.

Mahathir Mohamad with prime-minister-in-waiting Anwar Ibrahim (L). Photo: Kyodo

Asrul Hadi Abdullah Sani, director at consultancy firm BowerGroupAsia, said he believed race relations had not improved since the election due to “political realities”, including Umno’s shift to the right since the election.

Apart from the Lembaga Tabung Haji kerfuffle, the government also has been forced to move swiftly to quell racial anxieties in other instances – most times involving discontent among the majority Malays. Last year tempers flared when a

Malay firefighter was killed while attending to fires at a riot near a Hindu temple.

The Malay ground was also the cause of the government’s decision to backtrack on ratifying two international statutes, after Umno leaders successfully pressed home their view – contested by officials – that the treaties would disturb long-standing special privileges accorded to the Malays.

Dealing with race, particularly the feelings of Malays, is a delicate dance for Pakatan Harapan.

The country of 32 million people, with 60 per cent of the population comprising Malays, has only known a Malay-dominated government since its independence in 1957.

Malaysia’s monarchy vs Mahathir: a battle for supremacy

The mantle of power previously was held by the Barisan Nasional bloc, which organised itself such that Umno – and consequently the Malay community – was dominant. Pakatan Harapan, on the other hand, came to power promising a new kind of politics where all parties would be equal.

The ruling bloc comprises Mahathir’s Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia (Bersatu); the Chinese-dominated Democratic Action Party (DAP) led by Finance Minister Lim; Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR), led by the prime minister’s putative successor Anwar Ibrahim; and the Islamist outfit Amanah.

Also supporting the alliance is Warisan, the ruling party in the semi-autonomous Bornean state of Sabah.

Handling race relations is made particularly tricky for Pakatan Harapan by the fact that it won the polls with only 30 per cent of support from Malays, with remaining votes mostly going to Umno and PAS. Some 95 per cent of voters of Chinese descent are reported to have backed Pakatan Harapan.

Malaysian finance minister Lim Guan Eng. Photo: Bloomberg

FIGHT TO BE MALAYS’ CHAMPION

Umno, hollowed out by defections and the troubles of its former leader

– the deposed premier now facing corruption charges – has sought to play up Pakatan Harapan’s strong support among the Chinese, creating the perception that Mahathir’s government is not interested in serving the Malays.

In their cross hairs is the DAP and their leader, Lim.

As the finance minister portfolio was held by a Malay during the Barisan Nasional years, the appointment of a non-Malay to the position has been used as an illustration of how the DAP wrested control of something that inherently “belonged” to the Malays.

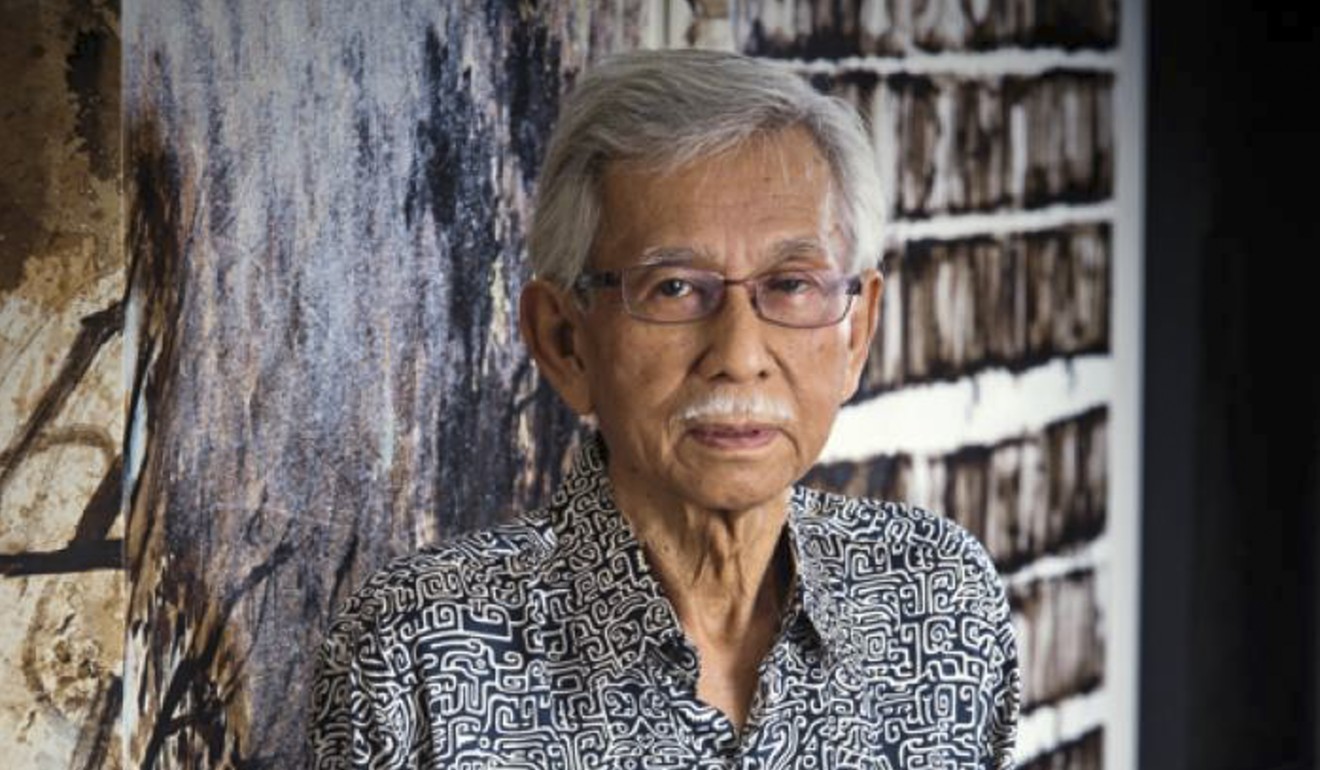

Daim Zainuddin, a top adviser to Mahathir and chairman of the prime minister’s special advisory panel, the Council of Eminent Persons, told This Week in Asia he had always expected that the Umno-led opposition would turn to fanning racial feelings, especially with allegiances among Malays divided “five ways” – to Mahathir’s Bersatu, Anwar’s PKR, Amanah, PAS, and Umno.

“The opposition will always exploit and take advantage, and the easiest is to play up race and religion,” Daim said in a Thursday interview.

Where’s Malaysia headed with its race-based preferential policies?

The 81-year-old, a one-time finance minister, said he hoped the Malays would “think rationally” instead of falling for the false narratives being propagated by Umno leaders. The challenge, Daim said, was to press home to the Malays the decrepit state in which Najib left the economy when he was ousted from power.

Last year’s shock election result is viewed by most analysts as at least partly to do with a wave of “anti-Najib” sentiment linked to his alleged involvement in the multibillion-dollar 1MDB financial scandal.

The likes of Daim believe the rot was not confined to 1MDB, a state fund, and that the previous government’s excesses extended to other institutions such as Lembaga Tabung Haji.

“Who stole the money? You still want them [Najib’s government]? You can have them,” Daim said in the interview in his Kuala Lumpur office.

“Ministry of Finance buys [Tabung Haji assets] for 19 billion ringgit. You are not happy? Something wrong. Oh, [Umno says] MOF is Chinese. What Chinese? This is a Pakatan Harapan government. You have to think rationally. Only idiots believe these things, and there are too many idiots around I say.”

On the opposite end of the spectrum, Umno figures say establishment figures are free to call them names – but that will not stop them from talking about race and politics.

Razlan Rafii, self-styled “political street fighter”, is among a group of the party’s members – well known for their hardline, some might call extreme, view about race relations – who have come into the limelight since last year’s defeat.

These one-time second-tier figures have come to dominate Umno’s politics, after its more patrician leaders such as Najib and his top lieutenant Ahmad Zahid Hamidi were caught up in the prosecutors’ dragnet for alleged corruption.

D.A.P. IN THE CROSSHAIRS

Razlan, currently under investigation for suggesting members of the Chinese-centric DAP should be “shot”, says he was using hyperbole to describe the true feelings of Malays – that the DAP was calling the shots in the Mahathir government, and was forcing the prime minister to abandon the Malay agenda.

“The DAP wants a Malaysian Malaysia. They want to make all of Malaysia equal. They want to demolish Malay special rights and the priorities of Muslims,” the fast-talking Razlan told This Week in Asia.

While accepting that Mahathir was a revered figure among Malays, holding the moniker “Father of Development”, he claimed the elder statesman was “very different” in his second stint in power. “We accept, he was the father of development … but now he is working with the DAP, they are controlling him.”

His party colleague Lokman Noor Adam espoused similar claims. Political watchers say their narrative catches on among rural Malays because it is simple.

Their mantra is that the DAP, which preaches multiracialism as its core tenet, covertly wants to unwind the affirmative-action policies for Malays that have existed since bloody riots between the majority ethnic group and the Chinese in 1969. The 50th anniversary of the sectarian violence, which claimed hundreds of lives, is on May 13.

Anxieties about Mahathir’s new Malaysia go deeper than race

The special rights conferred to the Malays after the riots, along with the constitutional position that Islam is the “religion of the federation” and the sacrosanct position of the constitutional monarchs, will be under threat if the DAP remains in power, Lokman and Razlan constantly said in separate interviews.

Said Lokman: “DAP’s brand of multiracial politics is bulls**t. The DAP won because they proved to the Chinese community that only they are willing to fight the Malays, and that they are the only ones willing to fight for equal rights, which is against the constitution.”

Like Daim, Syahredzan Johan, an ethnic Malay who is in the DAP, said he expected no less than such shrill talk as Umno found itself with its back against the wall a year after the May 9 ouster.

Apart from castigating Umno, coalition insiders had not gone on attack mode enough, he said. His party, founded in the 1960s as a Malaysian offshoot of neighbouring Singapore’s People’s Action Party – in power still, in the Chinese-majority island state – has long been a bogeyman trotted out by Malay leaders to shore up support in their base. Said Syahredzan: “The narrative is there, it is alluring but it is not true … we have not done ourselves any favours by not pushing back hard enough [both in the DAP and in the coalition] to say this is not a DAP government, this is a consensus government.”

Umno’s Lokman Noor Adam. Photo: Tashny Sukumaran

Malay leaders from other Pakatan Harapan parties say the onus is on the leaders of their respective parties to beef up confidence in the ruling coalition among the majority ethnic group. “The Malay voters want to see Malay leaders protect and uphold the rights of Malays … you need to be seen to be doing it,” said Haniza Talha, the women’s wing chief of PKR.

Marzuki Yahya, a member of Mahathir’s Bersatu party and the deputy foreign minister, suggested the government – facing relentless questions about the DAP’s role in it – should not shy away from reminding Malay voters about the excesses of Najib’s administration.

“It was Barisan Nasional and Umno that gave away assets to foreign countries, engaged in corruption … that’s the worst thing. The Malays should band together to fight corruption with this government. In Islam corruption is wrong, it’s a sin.”

THE LEADERSHIP QUESTION

Some in the administration, meanwhile, say the country’s heightened racial quandary since the election may have more to do with the splintering of Malay support within Pakatan Harapan, rather than the incendiary comments from the likes of Umno’s Razlan and Lokman.

One part of the equation is the question of who will be the next prime minister.

As part of a coalition agreement, Mahathir, 93, must hand power to

within two years of the election. Mahathir, however, has not named a succession date, and Anwar’s public stance is that putting a time limit on Mahathir’s premiership would make him a lame-duck leader.

Still, political courtiers – among them aides to ministers and backbenchers – suggest the long-term solution to long-term anxieties among the Malays should be a political realignment that removes the splintering of the group’s political class.

The DAP wants a Malaysian Malaysia. They want to make all of Malaysia equal.

“You may play these games for short-term political gains … moving your pieces around, hedging your bets, but in the meantime the Malays are wondering, are you going to stand up for me or are you more interested in your old rivalries?”

The situation has not been helped by suggestions within the commentariat that there are now other contenders seeking to be prime minister – which would run against the coalition agreement.

Among the names being touted are Economic Affairs Minister Azmin Ali, a long-time Anwar ally who has bristled at the veteran politician since the election, and Muhyiddin Yassin, the home affairs minister.

Bersatu’s Marzuki, asked to comment on the question of cohesion among Pakatan Harapan’s Malay leaders, said questions about a looming leadership tussle were a “weapon by the opposition to split us”.

“Do you see a clash every day? We decide things together. Different ideologies, but it doesn’t mean we are divided.”

Sorry, Singapore: Malaysia sells assets to cope with US$245 billion debt

For Anwar, Malaysian political punters’ overwhelming favourite as Mahathir’s successor, the challenge will be to deliver on his decades-old promise of a more equal Malaysia to his broad progressive and urban base, while not alienating rural Malays.

The democracy icon’s erstwhile clashes with Mahathir centred on his view of a fairer Malaysia. Speaking at a by-election rally in April, comments by the 71-year-old suggested he had no plans to sing Umno’s hardline tune, even as they assailed his multiracial stance. In that contest, he backed an Indian candidate who eventually lost out to Umno’s top leader, Mohamad Hasan.

“Malays will survive if we have clean, incorruptible, good leaders. Not just the Malays will survive – the Chinese, Indians and Kadazans will, too,” Anwar said. “But if we choose corrupt and cruel Malay leaders the Indians, Chinese and Malays will not survive.”

THE PRICE OF FAILURE

Analysts meanwhile say that if Pakatan Harapan does not crack the code on how to keep to its multiracial beliefs while also assuaging Malays’ anxieties, the biggest consequence would be a derailment of the bloc’s extensive reform agenda.

The Lembaga Tabung Haji plan is just a small part of the Mahathir government’s sweeping vision to reform key institutions that it says had atrophied during Najib’s time in power.

From commercial entities such as the sovereign wealth arm Khazanah Holdings and state palm oil firm Felda to government bodies like the judiciary and the attorney general’s chambers, the administration has put in place new personnel – based on merit.

The major sacred cow, affirmative-action policies for Malays, will also need to be reformed for the government to meet its long-term goal of reining in the fiscal deficit and trimming social welfare.

But these reforms could be put on the back burner if the government becomes too nervous about Malay support.

Mahathir’s long-time confidante Daim Zainuddin. Photo: Daim Zainuddin

“The government’s nervousness about its support among ethnic Malays makes it more likely to resort to economic nationalism,” said Peter Mumford of the Eurasia Group consultancy.

“This is bad news for economic reform and efficiency broadly, but poses particular risks for foreign investors and companies hoping to expand their market share in Malaysia.”

Daim, referred to in political circles as Malaysia’s “Oracle”, said “we would like to plead with Malaysians to think logically” instead of buying in to racial rhetoric.

“We are here together. We have to build up the strength together … there is no other alternative than living together in a multiracial society”.

Mahathir, who shocked the country with his 2016 entente with decades-old enemies in the DAP, this week sought to emphasise that Umno’s parochialism would imperil the country.

Speaking at a youth conference, he urged Malaysians to pursue the path of pragmatism.

He said: “We have our own sets of prejudices within our people but by and large, we have come to accept that any attempt to champion one race or religious group at the expense of the other will result in destruction of all that we have worked hard to build.”

This is the third of a four-part series on Malaysian politics a year on from the Pakatan Harapan coalition’s historic election victory on May 9, 2018

SOUTH CHINA MORNING POST

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.