Although our Anti-Fake News Act 2018 has been highlighted in an ongoing British parliamentary inquiry as an example of the phenomenon being politicised and resulting in censorship, a number of UK editors are surprisingly throwing their support behind a new anti-fake news initiative for their country.

In a statement, the Society of Editors (SOE) said last week that it is supporting an initiative by the National Literacy Trust to help children make more sense of the modern news landscape.

Citing the literacy trust’s report, the society’s executive director Ian Murray said “School-aged children and also young people find it difficult to determine fact from fiction in today’s blizzard of news sources when so many adults face the same difficulties.”

The report, Fake News and Critical Literacy, was compiled by the Commission on Fake News and the Teaching of Critical Literacy Skills, run by the All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Literacy. The report finds that:

- Only two percent of children in the UK have the critical literacy skills they need to tell if a news story is real or fake;

- Half of children (49.9 percent) are worried about not being able to spot fake news;

- Two-thirds of children (60.6 percent) now trust the news less as a result of fake news;

- Two-thirds of teachers (60.9 percent) believe fake news is harming children’s well-being, in terms of increasing their anxiety levels; and

- Half of teachers (53.5 percent) believe that the national curriculum does not equip children with the literacy skills they need to identify fake news.

The report also noted that “the online proliferation of fake news is also making children trust the news less. Almost half of older children get their news from websites and social media, yet only a quarter of these children actually trust online sources of news.

"Regulated sources of news, such as TV and radio, remain the most used and the most trusted by children and young people in the UK,” it read.

Based on these key findings, the SOE concluded that it needs to “ensure responsible media organisations play their part in helping teachers and parents to have the tools to enable youngsters to start to make decisions about what to believe and what to ignore at a much younger age.”

A threat to democracy

The UK parliamentary ‘fake news’ inquiry was launched by the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee in January 2017, arising from the growing phenomenon of widespread dissemination and acceptance as fact stories of uncertain provenance or accuracy.

Launching the inquiry, committee chair Damian Collins said that ‘fake news’ is a threat to democracy and undermines confidence in the media in general.

In a written submission to the inquiry, the Helena Kennedy Centre for International Justice at Sheffield Hallam University pointed out that, “'Fake news' has been used as a catchphrase by those in power to demean those who seek to speak out against them, or just negatively against them.”

The centre cautioned against allowing regulations targeted at a particular, politicised definition of 'fake news', such as our own Anti-Fake News Act 2018, as it would lead to censorship.

Fake news, the centre said, can be most generally defined as "news articles that are intentionally and verifiably false, and could mislead readers," or simply “misinformation”.

But in our Anti-Fake News Act, ‘fake news’ is defined as “any news, information, data and reports which, in part or wholly, are false, whether in the form of features, visuals or audio recordings or any other form that can portray words or ideas”.

Given the impossibility of deciding upon an agreed, universal definition of 'fake news' that would allow balanced and proportionate regulation, the Helena Kennedy Centre believes the prevention of public harms through such regulation could give rise to a host of legal problems.

As such, it strongly advised against laws that outright prohibit 'fake news', and stressed that education is absolutely key – in terms of nurturing critical thinking skills among the populace to identify fake news, which should be developed in formal education from a young age.

Committed to repeal?

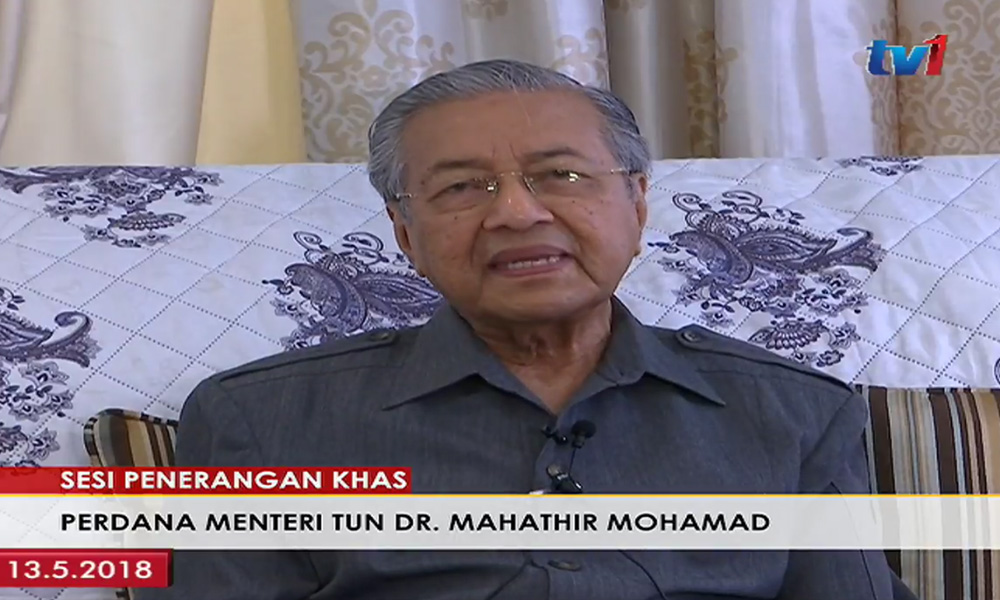

Dr Mahathir Mohamad, who was then leading Pakatan Harapan to dislodge BN from office, was himself targeted under the Anti-Fake News Act, which was bulldozed through Parliament in the dying days of Najib Abdul Razak’s rule.

Mahathir claimed that even officers from the Attorney-General's Chambers were confused about the bill. "It's clear they are confused and do not know the purpose of this law, except than to serve a political agenda,” he told reporters then.

The reason for formulating the new law, Mahathir added, was only to give the government more powers to arrest its critics. Accordingly, one of the key points of Harapan’s election manifesto was to get rid of the Anti-Fake News Act and other oppressive laws.

However, soon after taking office, Communications and Multimedia Minister Gobind Singh Deo said that it may take two to three months for the government to repeal the anti-fake news law. This is because the ministry might not have the time to complete the paperwork needed when the Dewan Rakyat sits on June 25. However, this first sitting of the country’s 14th Parliament has now been fixed for July 16.

Weeks after the Anti-Fake News Act was passed, an individual - Danish national Salah Salem Saleh Sulaiman - was convicted under the Act. Salah pleaded guilty to maliciously publishing fake news in the form of a YouTube video on the recent shooting of alleged Hamas militant Fadi al-Batsh in Kuala Lumpur.

And barely a month after the May 9 general election, the High Court in Kuala Lumpur dismissed Malaysiakini’s leave application to nullify the Act on grounds that the action brought was premature, as the portal had not been charged under the law.

This is akin to the police saying it cannot act upon a complaint on a murder that is about to take place, simply because the victim is not yet dead.

BOB TEOH is a media analyst. -Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.