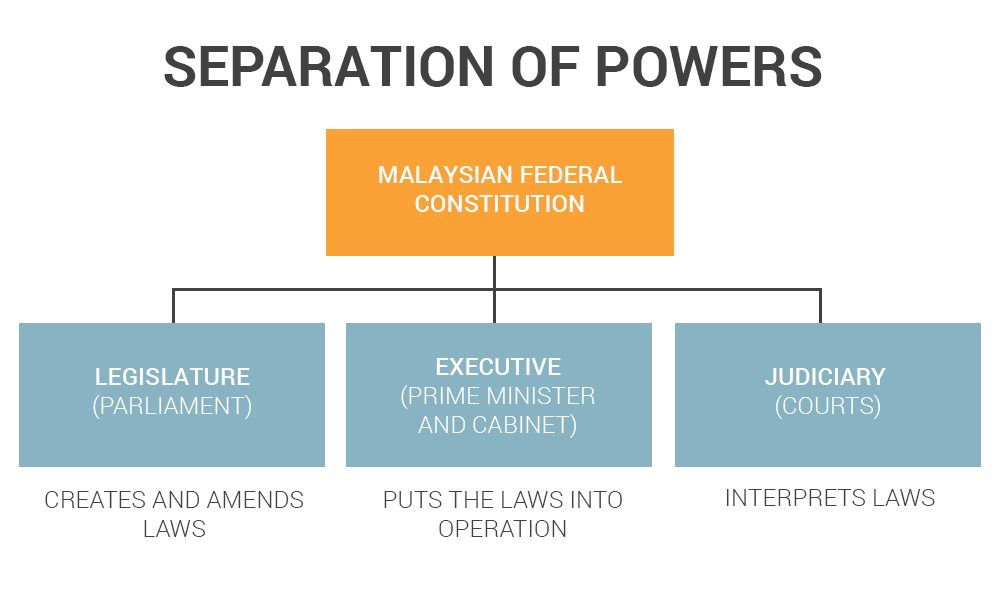

ANALYSIS | On Sept 11, 2019 - last week - the Malaysian Parliament turned 60. Under the doctrine of the separation of powers, Parliament does not only enact laws but also plays the role of check-and-balance against the executive branch of the government.

However, over the years, Parliament has been deemed the executive’s “rubber stamp”, which approves almost any bill proposed by the executive without alteration. One measure of the executive’s influence over Parliament is the percentage of Members of Parliament on the government's payroll in the Lower House, the Dewan Rakyat. This measure is called "payroll votes".

Payroll votes refer to MPs holding positions in the executive, such as cabinet ministers and deputy ministers. They are expected to vote for the ruling party to support the executive.

Research by Malaysiakini and Penang Institute found that the percentage of payroll votes in the Dewan Rakyat grew in the period of 1974 to 2004 before declining in the last 11 years. (Data for the years before 1974 are incomplete.)

At its highest point - under the fifth prime minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi - payroll votes made up 41 percent of the Dewan Rakyat. This meant that almost half of the Dewan Rakyat was on the executive’s payroll. Today, about one-fifth of the Dewan Rakyat comprises payroll votes.

The research only covers the number of ministers, deputy ministers and parliamentary secretaries in the first parliamentary sitting after a general election. It does not include cabinet reshuffles and MPs appointed as directors and senior managers of statutory bodies and government-linked companies, due to insufficient data. This means the government’s grip on Parliament is likely to be stronger.

In 1974, when then prime minister Abdul Razak Hussein formed his second cabinet after the fourth general election, 28 percent of Dewan Rakyat was made up of payroll votes. Out of 154 MPs, 43 held government posts

This figure expanded two-fold in the next two decades. In 2004, 41 percent of Dewan Rakyat MPs served in the Abdullah Ahmad Badawi administration. This sizeable expansion came after BN secured an overwhelming victory in the 11th general election that year. The coalition won 199 of 222 parliamentary seats - a supermajority. Of the BN MPs, 92 were appointed ministers, deputy ministers or parliamentary secretaries.

The executive’s presence in Parliament declined after the 2008 general election when BN lost its two-thirds majority in the Dewan Rakyat. It was also the year the executive decided not to appoint any parliamentary secretaries. A parliamentary secretary’s duty is to assist ministers and deputy ministers in the discharge of their duties and functions.

The decision not to appoint parliamentary secretaries slashed the number of payroll votes from 92 in 2004 to 52 in 2008. The downtrend in payroll votes percentage continued after the 2018 general election when Malaysia witnessed its first-ever change of government.

The total number of ministers and deputy ministers under the Pakatan Harapan and Parti Warisan Sabah (Warisan) government is 50, making up just one-fifth of the total number of 222 MPs in the Dewan Rakyat. It is also the lowest percentage of payroll votes in the Dewan Rakyat since 1974.

High payroll votes affect good governance

Even so, at 22 percent, it is higher than the 15 percent limit proposed in a research paper published by the Public Administration Select Committee of the House of Commons in the United Kingdom. The proposal was for the House of Commons, the Lower House of the UK Parliament. It is one of the few academic research papers published worldwide on the issue. No such study has been conducted on the Malaysian Parliament, as yet.

The UK paper titled "Too many ministers?" says that the size of the payroll votes affects good governance as it limits the number of MPs who are able to scrutinise the government effectively.

“If you have a big majority, it is very easy to be strong because of your majority and your payroll vote is so large you can just ignore anything, even if it has total commonsense behind it; that is the position governments with large majorities get into,” the report quotes former UK prime minister John Major as saying.

Sunway University political scientist Wong Chin Huat said it is more meaningful if payroll votes are calculated as a percentage of MPs from the ruling coalition, instead of all MPs. This is because only MPs from the ruling coalition can get on the executive’s payroll.

In the Westminster parliamentary system, MPs who are on the executive payroll are known as the "government frontbenchers" whereas ruling coalition MPs who do not hold any governmental office are the "government backbenchers".

Going by Wong’s measure, the proportion of ruling party MPs in Malaysia on the federal payroll has remained consistent at about 40 percent since 1978.

However, in 1974, that figure was much lower at 32 percent. At its peak in the year 1990, almost half of BN MPs held government positions. In the first parliamentary sitting after the change of government, 40 percent of the ruling coalition MPs were payroll voters.

Today, the percentage is 36 percent after 14 MPs from Umno joined Bersatu. This is comparable to the British and Canadian parliaments.

Backbenchers subservient to the government

Wong believes parliamentary scrutiny on the government may decrease in both quantity and quality if the executive continues to rope in brilliant MPs into its fold. However, he stressed, the fundamental problem with the weak check-and-balance system in Malaysia is not the growing payroll vote, but a subservient government backbench.

Contrast this with the British Parliament, where backbenchers have greater freedom to act, including staging a backbench revolt - that is to vote against its own government’s bill - with little consequence, he said.

“The UK’s current opposition leader, Jeremy Corbyn, voted against his own party whip’s instruction 421 times when Labour was in government from 1997 to 2010, 33 times per year on average. He was neither sacked from the party nor denied candidacy in subsequent elections,” Wong said.

As such, he described the sacking of 21 government backbenchers by current UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson for preventing the UK from leaving the European Union without a deal is “shocking”.

“Because the backbench revolt is not a cardinal sin, but a common phenomenon in British politics,” he explained.

Wong said in the UK Parliament, backbenchers compete among one another to become frontbenchers. Using a sports analogy where weak teams are demoted to a lower division, he said weak frontbenchers can be demoted to the backbench and good backbenchers can be promoted to the front. This incentivises MPs on both sides of the House to perform.

This doesn't happen in Malaysia, where the government backbenchers are viewed as "government supporters" instead of playing the role of checking the executive, he said, adding that this culture is also absent on the opposition side of the House because the opposition has never had a proper frontbench in the form of a shadow cabinet.

During BN’s time, the Malay name of the BN backbenchers' club was “Kelab Penyokong Kerajaan Barisan Nasional”. When Harapan took over, it was renamed as the Backbenchers Council (Majlis Ahli-Ahli Backbencher).

What is the ideal size for payroll votes?

Backbenchers Council chief coordinator Ong Ooi Heng said the renaming shows that the Harapan backbenchers understand that they are not there to blindly support the government. He said Parliament’s ability to check the government depends on how well backbenchers know their role.

Backbenchers can play two distinctive roles - which are to support and stabilise the government or stage a revolt - which will result in a collapse of the cabinet, he said.

“Currently, four out of 10 government parliamentarians are on the (federal) government’s payroll. But in order for the four to secure their jobs, they have to get the support of the remaining six. Or else the cabinet will collapse,” Ong said.

Ideally, he said, the ratio of frontbenchers to backbenchers is 1:2 to prevent the executive from becoming too powerful in Parliament.

“If we have the majority of the MPs - say two-thirds of them - becoming ministers, deputy ministers and parliamentary secretaries, the remaining one-third of them can hardly make any difference or worse (it will be) as if they do not exist,” he said.

Sunway University’s Wong believes that instead of thinking of an ideal number of frontbenchers, the question to ask is whether positions in the cabinet are created on portfolio consideration or merely to satisfy political calculations.

He added that the growth in payroll votes also means taxpayers are saddled with higher salary bills.

“Can Malaysia do with fewer ministers and deputy ministers? Yes. Do we need more (payroll) MPs, given that our population is now 32 million? No. No matter how many people a country has, it is going to need only one foreign minister, one defence minister and one home affairs minister. There is absolutely no need to have more frontbenchers because you have a big population,” Wong said.

Putrajaya’s long shadow over Dewan Negara

The influence of the executive over Parliament is not only evident in the Lower House but also in the Upper House - the Dewan Negara. The Yang di-Pertuan Agong has the power to appoint a certain amount of senators on the advice of the federal government, according to the Federal Constitution.

In 1959, there were a total of 38 senators, of which only 16 of them were appointed on the advice of the federal government. The number of federal-appointed senators surpassed the state-elected senators in 1964, after a constitutional amendment. Today, there are a total of 70 senators in the Dewan Negara.

Following constitutional amendments, the executive is allowed to advise on appointments of 44 senators, of whom four are from the federal territories of Kuala Lumpur, Labuan and Putrajaya.

As such, the federal government has a say in the appointment of more than half of all senators, while the remaining 26 are elected from the other 13 states, two from each state. The state assemblypersons nominate candidates and vote on whom they want to send to the Senate.

The process of appointing senators was highlighted in the "Dewan Negara Reform Report" released by the Senate Reform Working Committee in July. The report noted that the Dewan Negara was full of senators who represented political parties.

As such, the transparency and effectiveness of the Dewan Negara were questioned as the senators were forced to toe their party's line or were pressured when making decisions, it said.

“It means that any decision that was made was assumed to follow the ideology of the political party but not the interest of the people,” the report reads.

‘Let candidates apply to be senators’

To address this issue, the committee recommended providing clearer guidelines on the appointment of senators and to provide opportunities for qualified candidates to apply for senatorial appointments. It also suggested the establishment of an Independent Appointment Committee to evaluate qualified candidates for senatorship.

The report does not call for a review of the number of senators whose appointments are made on the federal government’s advice. Senate Reform Working Committee chairperson Yusmadi Yusoff said that it is a matter of quality over quantity.

“The most important thing is not the number (of senators appointed on the advice of the federal government) but the quality of debate (in the Dewan Negara),” Yusmadi said.

He argued that there should be an adequate support system for the senators through the establishment of a parliamentary academy for research, training and publication purposes.

Yusmadi also stressed the importance of including representatives from minority and special interest groups, such as the disabled, indigenous people as well as women and youth, into the Dewan Negara through the improved appointment process. He also recommends forming an advisory committee to advise the prime minister to determine the best candidate from the various interest groups.

The report also makes other recommendations, including making better use of the senate select committees to deal with issues facing the country and allowing the senators to originate bills to ease the burden on the Dewan Rakyat.

It also suggested the establishment of a Select Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills, a review of the tenure of senators and ensuring gender equality in senatorial appointments.

One of the most important recommendations the report proposed is the reinstatement of the Parliamentary Services Act 1963, with enhancements to emphasise the sovereignty and independence of Parliament.

The Act allowed Parliament to conduct its own administration, staff hiring and financial matters. It was repealed in 1992, allowing the executive to decide on such matters.

Dewan Rakyat deputy speaker Nga Kor Ming once described that the present Parliament as “subservient” to the executive and that Putrajaya has committed to reinstating the Act.

'Mixed electoral system is the only way'

Even if the Act is reinstated, it will not dilute the impact of the party whip culture deeply rooted in the Malaysian Parliament. Unlike the UK Parliament, where MPs can vote by conscience, Malaysian parliamentarians have much less autonomy and will almost always vote along party lines to avoid party censure.

In 2005, former Sri Gading MP Mohamed Aziz and Kinabatangan MP Bung Moktar Radin from BN were censured by the then BN party whip Najib Abdul Razak for attempting to support an opposition motion. The duo later tendered an apology to Najib for their actions.

This subservience is driven by the current first-past-the-post (FTPT) election system and the coalition politics necessitated by ethnoreligious segmentation in Malaysia, Wong, the political scientist, said.

It is different from the UK, where the FTPT system is practised but political parties do not form coalitions before an election.

This, Wong said, allows political parties there to contest freely, as long as they have the machinery which in turn leaves more power for the local party leaders to determine their candidates.

The need to negotiate with allies to form a coalition means power is centralised within political parties, leading to a hierarchical and subservient culture, including the party whip culture.

Thus, he said, the only solution is to introduce a mixed electoral system which allows voters to vote for two types of parliamentarians, for FTPT constituencies and those on party lists.

“The top leaders of (political) parties will get to pick candidates on the closed lists and can place their loyalists in safe positions. Concessions can be made to divisions or branches to nominate the most hopeful candidates, even if some of them may be mavericks,” he said.

A senate election

As for Dewan Negara, Wong said that there should be a full election for senators under a closed list-proportional-representation (List-PR) system, while Sarawak and Sabah, including Labuan, should be given one-third of the seats to ensure their veto power on constitutional matters.

He explained that the List-PR system will ensure state interests are represented and the party divide will not turn into regional divides and hence threaten national unity.

“List-PR would allow parties to appoint technocrats, who can then be nominated as ministers, to the Senate. This is more superior than the current avenue that allows the executive to parachute in any new talents. This is not only completely free from voters’ control but also makes the Senate a rubber stamp and consequently subverts the bicameral design,” he explained.

Backbenchers’ Council chief coordinator Ong agrees there should be an election for the Dewan Negara, with a proportional representation system for the same reason. However, he worries that such a move will draw criticism as it will be seen as an attempt to erode the Agong’s power to appoint senators.

“We could start with a portion of the Dewan Negara with the proportional representation system and we will see whether it is acceptable for society,” he said.

The Dewan Negara Reform Report also acknowledges the importance of having elections for senators. But until that happens, Yusmadi stressed that there should be more transparency in senate appointments by having interviews and other processes to ensure suitable candidates.

Ultimately, the goal is to strengthen Parliament so it can play its role to check the executive for the public's good.

Ong hopes that society can be more concerned about the Parliament’s integrity, which in turn can pressure MPs to speak up for the rakyat and not their parties.

He said civil society can also play a more active role, including lobbying political parties on candidate selection, he said.

“Do not let the political parties dominate the process of selecting the candidates. Civil society has to compete against political parties to pressure the political parties to come out with candidates who can meet the requirements of civil society,” he said.

LEE LONG HUI is a Malaysiakini team member while KENNETH CHENG is a Penang Institute researcher. The above is written in conjunction with Parliament's 60th anniversary. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.