Malaysians are gearing up for heated polls in the 14th general election. Caretaker prime minister Najib Abdul Razak and his party Umno, which has in office since 1957, aim to perpetuate their tenure.

Many do not fully realise, however, that for the past three years there have been intense battles in the courtrooms, which continue to cast an unconstitutional shadow over the election. Minimally, the legal challenges have raised serious questions about the fairness of the electoral process and the nature of political power in Malaysia.

When Malaysia’s electoral reform process began in 2007, the focus was to head to the streets to draw attention to the country’s uneven electoral playing field.

Bersih moved from an opposition vehicle to a broad civil society movement. From 2011, the movement was led by lawyer Ambiga Sreenevasan, whose leadership brought out thousands of Malaysians to rallies, and culminated in a People’s Tribunal in 2013, outlining serious irregularities in that year’s election.

That year, the chair of Bersih was taken over by Maria Chin Abdullah, a social activist, who ironically spearheaded fierce legal challenges over the electoral process until her resignation last month to stand as a candidate.

A broad range of stakeholders, including pro bono lawyers, opposition parties, state governments and, importantly, ordinary voters, have instituted an unprecedented number of legal challenges over electoral reform in Malaysian courts.

Obstacles to EC

While the legal cases were not able to halt the delineation process, they have provided obstacles to the Electoral Commission and exposed breaches in standards of electoral integrity, as detailed below.

Given the complexities of the change in strategy from the streets to the courtroom and the fact that most of the cases have received limited media attention, this article focuses on how legal contestation is an integral part of GE14.

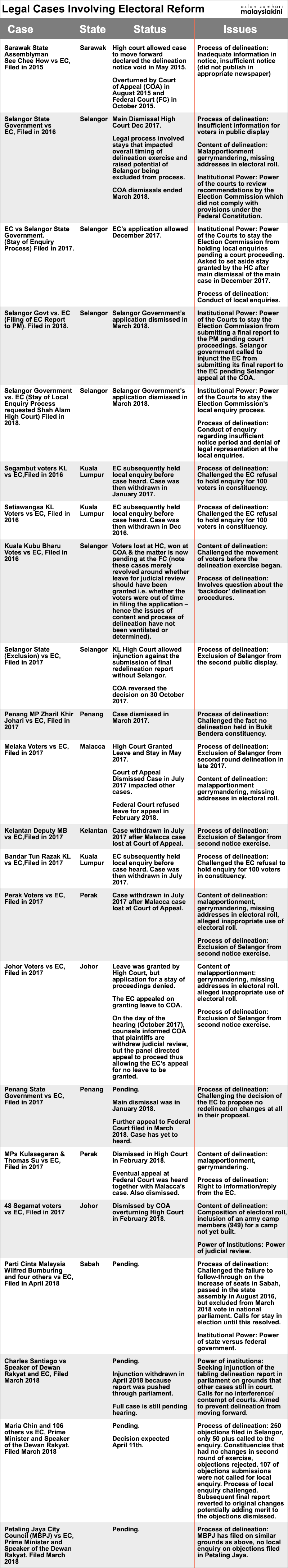

The table below summarises the legal cases over the past three years. Broadly, the cases have involved three issues: the content, and the process of the delineation exercise, and even more fundamentally, the power of different political institutions to make decisions on elections.

News reports to date have focused primarily on the content of the ‘front door’ delineation, based on the report submitted to parliament in March 2018. Concerns have rightly swirled around malapportionment (inequality in representation), gerrymandering (unfair drawing of boundaries) and the integrity of the electoral roll.

One case, Kuala Kubu Bharu voters vs EC, has also touched on the ‘backdoor’ delineation, the non-transparent movement of voters between constituencies. Not only have these cases served to further mobilise the public over these concerns, with detailed documented studies by Bersih to show the unfairness of the delineation process, the discussion has also been put on the public record.

The detailing of the manipulation of the electoral system to advantage the incumbent has provoked an unprecedented number of objections by the public to the delineation (as detailed in the EC’s own report).

Furthermore, the High Court decision in December 2017, Selangor government vs EC, has acknowledged that malapportionment and gerrymandering have taken place. This may seem like the obvious, but it serves to put on legal public record structural imbalances in the electoral system and is an acknowledgment within the system of the unfairness in the delineation.

The most apparent effects of the court cases involve the second realm, the impact on the delineation process. The legal cases have forced stays on the part of the EC, with the most impactful being the Selangor government vs EC case.

The stay was removed in Dec 2017, but it forced the hands of the EC for over a year, as they opted to move ahead in the national second display exercise (a constitutional 30 days requirement to make the changes public and open to objection) without the state of Selangor, following a procedure that did not conform to the past or inclusiveness of the country as a whole.

The failure to properly follow through in the delineation process regarding the increase number of seats in Sabah – passed at the state level in 2016 but not forwarded to parliament this year – is another example of inconsistencies in the delineation process and is now being challenged.

Legal contestation also forced the hand of the EC to carry out local enquiries, as occurred, for example, in Segambut and Setiawangsa. The challenges aimed to make the EC more accountable in its engagement with voters and sharing of information.

In the latter, there was little success in outcome, but the court proceedings in the Selangor government case revealed that the EC allegedly destroyed previous electoral rolls, raising questions about its professionalism.

In fact, the EC did not come off well in many of the arguments it presented, as it appeared to be what its critics charge it with, lacking independence and on a political mission for the dominant party Umno.

An example of this is the response to the Segamat postal voters, where there is no physical building but 929 army camp voters listed. Postal votes have traditionally been used to buttress support for the government. The EC repeatedly failed to present explanations when queried on why it opted to significantly expand malapportionment, broaden the use of gerrymandering and dismissed concerns about the electoral roll, opting for a strategy of denial and dismissal.

In the final submission, the EC reverted back to the original proposals that were challenged both in the courtroom and by citizen objections, after it had initially proposed counter proposals to appease some concerns about the perceived unfairness in the second display exercise.

The EC’s behaviour suggests ‘bad faith’ as well as contempt for calls for greater fairness in the electoral process. The legal cases helped expose how the EC responded to the public.

The thorniest issue involves what the cases raised about the relative power of different institutions. Here there are multiple important dimensions. The first involves the relationship between the EC and the executive, other branches of government, parliament and the judiciary.

Non-independent

The court proceedings often showcased a non-independent EC. Repeatedly, the EC – a constitutionally-mandated body – came off as ‘the government’ rather than as a professional autonomous (or even semi-autonomous) body, the international standard for electoral integrity. With the EC reporting directly to the prime minister, the court cases documented the EC’s political colours.

Given the political nature of these cases, the relationship between the judiciary and the executive was also centre stage. Recent cases in the courts – particularly Semenyih Jaya Sdn Bhd v Pentadbir Tanah Daerah Hulu Langat in May 2017 and Indira Gandhi a/p Mutho v Pengarah Jabatan Islam Perak & Ors in January 2018 – have brought to the fore the power of the courts to review legislation and the executive, the idea of judicial review.

Many of the cases called openly for the courts to review the content of the delineation exercise in a meaningful manner. While the High Court in the Selangor government vs. EC case did acknowledge serious problems in 2016, it was bound by a decision at the Court of Appeal in Malacca and MP Kula Segaran cases that prevented addressing the substance as the delineation was still not then passed by parliament.

Throughout, the court decisions relied heavily on technicalities to dismiss meaningful engagement with the content of cases, holding that the EC’s recommendations were not “decisions” capable of being reviewed and labelling the cases as “nonjusticiable”.

Some critics have labelled Malaysia’s judiciary as “pliant” and not independent, and this lack of meaningful engagement with the content of the delineation could reinforce this perception.

Yet collectively, the EC cases show a more varied picture. There were tensions between judicial reticence and more asserted measures to protect the Constitution and fairness in the rule of law. Many of the decisions went against the government, accompanied by stays which pressured the EC to act.

In one violation of court protocol (also involving the Selangor government case), a representative of the Attorney-General’s Chambers stood up to challenge the judge after he had decided on an interim stay which favoured the plaintiff. This prompted the judge to reiterate his earlier decision in strong terms.

The relationship between the executive and judiciary was not always smooth in these legal battles. It is only at the upper courts – the Court of Appeal and Federal Court – where there was a 100 percent decision rate in favour of the government.

There were also areas where decisions not to recuse judges who sat on earlier decisions with similar parties – in the hearing of the 2018 Selangor government case involving the filing of the report to parliament – and in the rushed timing of the decisions in the past six months where questions are being asked about the political position of the courts.

A full assessment of the courts’ capacity and willingness to use their powers of judicial review cannot yet be made, however, because there are at least five election cases still pending.

Further cases on the delineation process and content will likely be filed, given the fact that the technicality that the delineation was not legal has been removed with parliament’s passage of the exercise.

A legal reckoning

The courts will face a difficult decision on whether to exercise their judicial review and decide on constitutionality of the delineation, and ultimately the constitutional validity of the elections themselves. The electoral legal challenges have pushed the courts toward a legal reckoning. In Malaysia’s history, no election has been called with so many legal cases on the elections itself outstanding.

Finally, the legal cases have also opened up unintended areas of contestation. Consider the recently filed Sabah case, which tests the power of the state assembly to decide on its numerical composition. It taps into the power of respective state and federal governments vis-à-vis each other, which is already a highly contentious issue in Sabah and one of the key themes in the coming state election campaign. As is often the case, contention leads to unexpected outcomes.

Many said Bersih’s legal strategy was doomed from the onset, that the courts could provide no meaningful check on electoral integrity.

These assessments are not correct, as judicial contestation did indeed significantly shape the process of the delineation, expose and reveal more about the content of the delineation and test relationships between Malaysia’s political institutions.

The importance of the courtroom battleground remains crucial in shaping the final election outcome and its legality.

This article was first published in New Mandala.

BRIDGET WELSH is an associate professor of political science at John Cabot University. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.