An estimated 1.1 million voters in the beautiful state of Sabah will potentially hold the balance of national power. With 25 parliamentary seats (26 including Labuan), or 12% of the Dewan Rakyat, Sabah will determine whether BN will win comfortably (or not).

Most certainly, Sabahans will decide the political future of their state, provide an assessment of Musa Aman’s 15 years as chief minister, and determine the state’s relationship with the federal government.

Sabah has traditionally been seen to be part of the BN’s ‘safe deposit.’ Yet this election, the potential for change is stronger than in recent elections. The feeling on the ground is palpably different, as below the surface of congeniality lies deep resentments coupled with even greater aspirations.

Below I outline a few factors that are shaping the Sabah campaign and are converging towards a result that will put Sabah very much on the national stage. Sabahans, however, are less concerned with what happens nationally than what happens in their own state, with local concerns and grievances paramount.

Sabah for Sabahans

Unlike Sarawak, the desire for greater state autonomy in Sabah has not been co-opted by the BN. In part, this is due to the fact that there has been no change at the state leadership level for over a decade and thus no real opportunity to bring in a new mandate. It is also a product of perceptions of BN component parties, who were earlier part of the pressure for Sabah rights in the 1980s, as currently selling out to federal power.

The many Sabah ‘federal’ ministers reinforce this perception. The 2013 general election witnessed some of the Sabah autonomy fever taking root, especially in the Western part of the state where Kadazan, Dusun and Murut (KDM) communities predominate. Numerically many of these seats – Keningau and Kota Marudu for example – had opposition majorities, but ultimately were won by the BN due to the splits in the opposition itself.

These splits are likely to persist, but they are taking a different form. The most important split in 2013 was between local and nationally-based parties, with the “national” campaign overshadowing local actors. This election, with Warisan led by Shafie Apdal and a strong cohort of younger leaders, there is a stronger local alternative.

Warisan has taken the mantle of the state autonomy call, joining Star led by Jeffrey Kitingan (who was served a bankruptcy notice this week which could potentially disqualify his candidacy). Warisan is contesting across the state and is especially strong on the east coast. It has working alliances with DAP and PKR, who themselves have prioritised local issues over national ambitions. Warisan’s broad narrative of Sabah representation is taking root on the ground and reaffirming state autonomy sentiments.

The splits on the ground remain, however. Many of the splits are personality based, as local factors in Sabah are strong. There are also many new parties and independents, who are being funded to divide the vote. Some of the new entrants in the KDM areas have strong local ties. These factors will shape close outcomes.

There is an important different ideological split this time. This involves long-standing tensions between the KDM communities and resentments of the immigrants who came since the 1980s, many illegally. Sabah’s Warisan opposition is trying to forge cooperation between KDM leaders and the Muslim bumiputera communities in the West. Some of the KDM parties reject this cooperation, as they continue to feel angered by political displacement of the Project IC exercise.

Ironically, Warisan is trying to move beyond one of the legacies of the Mahathir era in this election, to bring Sabahans of today together across communities. There is understandable resistance, as the past continues to shape the present and as Sabahans themselves reflect on what sort of Sabah they want.

Local ethnic resurgence

Sabah is a complex multi-ethnic mosaic of over 35 different communities, with arguably the most cordial ethnic relations in Malaysia. Yet, ethnic politics is a powerful factor in Sabah. Rather than the broad national framework of Malay versus non-Malay or Muslim versus non-Muslims, local ethnic identities, tied to strong family-based networks, are more important.

We see, for example, strong Suluk and Bajau sentiment behind Warisan in the east coast, and similar loyalties in the KDM areas. These communities are fighting for their place in Sabah, with long-standing perceptions of displacement and simultaneous demands for stronger and fairer representation. Much of this ethnic mobilisation is among the young, under 40, who are demanding inclusion, respect and opportunities.

Key is where these demands are being directed, either at the federal government, the BN or against other communities within Sabah. Sabah’s opposition faces the challenging task of bringing together this anger and making sure that that the anger is not directly internally, building trust across ethnic communities. The BN is relying on distrust internally to win out. Warisan and other opposition parties are hoping that the anger against the BN will predominate.

The Sabah BN has always had the advantage in that it is seen to offer more ethnic inclusion for more communities. It is however losing its inclusive advantage. Sabah BN lost Chinese support in 2013, and this largely continues. The leadership in the KDM community has weakened, and with the purging of Shafie from Umno, support among other Bajau and Suluk communities within the BN has evaporated.

The BN has not made meaningful steps to strengthen ties with communities that feel excluded. In fact, the trend has been the opposite. The Sabah delineation exercise – which would have created 13 more state seats if parliament had passed it – built on this sense of recognition of different groups. It followed the pattern adopted for Sarawak, which led to a bigger win for the BN in their 2016 election.

In Sabah, the seats were not passed through parliament in part because of worries that the additional seats would undercut the chances to maintain power at the state level. It was a recognition that the BN did not have strong enough ties to some local ethnic communities. It also signalled broadly that the BN in Sabah was not about greater inclusion. The BN in Sabah is losing the inclusive mantle, a phenomenon that has happened in the Peninsular in the past decade.

Kings and dynasties

The solution the BN relies on is money – lots of money. Patronage Sabah-style, however, is also coming under strain. While it continues to be important in the rural and semi-rural seats, money is now the expectation, not the reward. Many Sabahans are asking for more than the token payout, especially the younger generation.

With a larger population, it is harder to maintain the personal touch, and with considerable “hard” development in terms of roads and services, the BN has less it can immediately deliver. Discussion centres on more abstract concepts such as the digital economy – not a market or a building (although sadly, many parts of Sabah still need them).

What contributes to the diminishing impact of patronage is disenchantment with parts of the BN leadership. Dynasty politics in Sabah is pervasive, especially in the ruling coalition. There is also a sense that many of the BN leaders have been around for too long, and political families are too entrenched. While many in the opposition also are part of the political elite, it is seen to be bringing in more new blood, and as such reinforcing the ideas of inclusion with its candidate selection. The long-standing tenures of the leaders have contributed to the BN’s erosion of support among ethnic communities as well.

If there is a main liability for the BN in Sabah, it is its leader, Musa Aman (photo). As chief minister, he has been traditionally very effective in bridging differences and assuring that the election machinery is oiled. This time around, his positive aura is not as strong. While the level of antipathy toward Musa is not as substantive as that projected toward Taib Mahmud in Sarawak, it is noticeably more intense than in the past.

Resentments are strong in the business community and within the ranks of Umno itself, as the principle of rotating power in Sabah has apparently been abandoned. And while Musa is not a ‘Najib man’, he has stayed in power with the prime minister’s support, despite many Sabahans close to Najib calling for Musa to be replaced. Thus, the BN faces double negativity – antipathy toward Najib and Musa. This negativity is particularly strong on the east coast, where the anger is highly personalised.

One strength for the BN, however, is that some of the negative toward Najib and Musa is offset by long-standing resentments toward Dr Mahathir Mohamad, whose legacy on bringing Umno into the state, reducing state power and reshaping the ethnic composition of the state is deeply resented. Yet, given the dominance of the local narrative, Mahathir’s role is less significant as compared to the Peninsular.

Religious identities

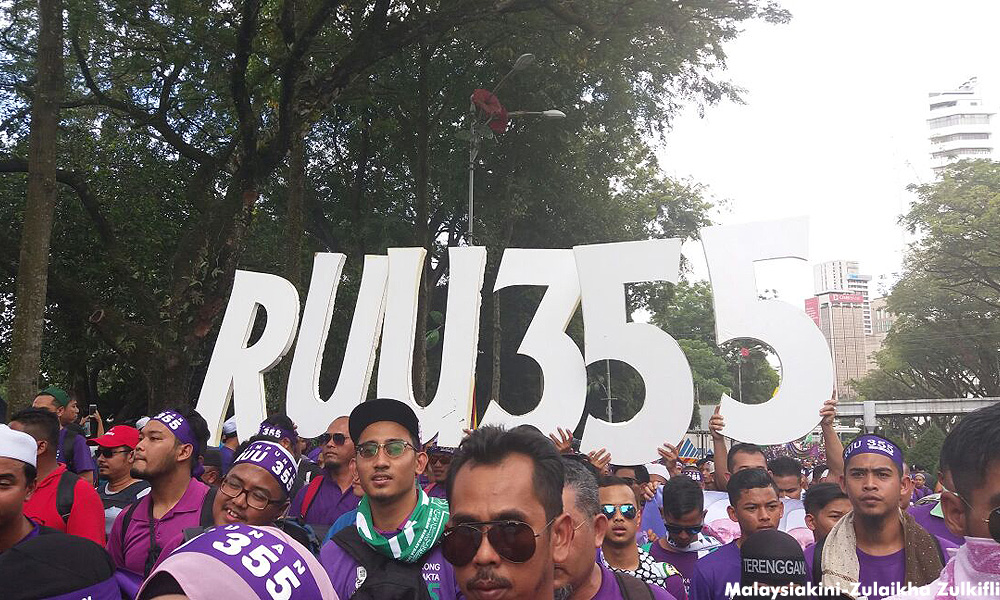

Where Peninsular politics does intervene is in the area of religious rights. Najib recently met church leaders on a visit to Sabah, addressing protections from the encroachment of Islamisation. Promises of resources abound (as Najib’s solution is largely to throw money at problems). These assurances have not fully assuaged concerns, as legal cases affecting East Malaysians not resolved positively and Najib continues to play politics with PAS with the introduction of the syariah criminal law, RUU355.

Sabah is the most Christian state in the country, and the more Najib is seen to pushing for an ‘Islamic’ agenda, the more this reverberates in Sabah itself. The argument made by local BN leaders is that their presence in the coalition provides protection for religious freedom but given how many of the concerns of Christians have been dismissed and the embrace of a more Islamic agenda by Najib, shaped by political calculations on the Peninsular, questions about the sincerity of the Najib government to maintain religious freedom for Sabah remains.

The disappearance of Pastor Raymond Koh, for example, is salient in Sabah. Any open move to ‘defend Islam’ by Najib will have blowback in Sabah, as trust in Najib has eroded in some quarters.

Swings and swag

How much trust has eroded is a crucial question. Local leaders on both sides of the divide will work hard to perpetuate two different views: the need to be in the BN tent versus the need to move away from Umno aka Najib/Musa and change the government.

As in the Peninsular, the attention is being centred on potential shifts in the support of Muslim bumiputera, who supported the BN in Sabah by an average of 80% last election. This election, there is a definite movement away from the BN, but how much of it is evolving. The assumption is that the more pro-opposition leaning Chinese and KDM communities will maintain their levels of support for the opposition around an average of 70% and 65% respectively.

This is not fully clear, but signs are strong that local dynamics noted above and long-standing resentments continue to resonate. Turnout levels may drop however, undercutting the support of the opposition, as it is in distant Sabah where costs to return to vote are high. Large numbers of voters in Sabah, especially younger voters, work away from home.

For change to happen in Sabah, it will require movement among all the communities, given the multi-ethnicity of the state as a whole. Nearly half of the parliamentary seats are competitive, and while the BN had a strong advantage at the state level - with the opposition needing to win an additional 16 seats and hold onto what they have - Sabah is one of the states where power is being meaningfully contested.

As elsewhere, both sides are confident. The BN is relying on old techniques to stay in office, as money will come pouring down on election day. Promises of ‘development’ have already started. Those in BN believe financing, splitting of opposition support and the pull of its leadership will be (more than) enough to secure a ‘safe’ victory. The opposition on its part feels they offer a stronger alternative compared to the past and have greater connectivity to local concerns. They hope to capitalise on BN’s weaknesses.

Many Sabahans are not registered to vote - around one million of the 3.5 million population - so the result will come down to 1.1 million of eligible voters. Sabah also has large numbers of undecided voters, so the election campaign itself will be important. Even with this uncertainty, signs are showing that Sabahans have a stronger sense of their own political power, and this in itself represents meaningful change. Whether this will translate at the ballot box is not yet a reality, but the potential is there.

BRIDGET WELSH is an Associate Professor of Political Science at John Cabot University in Rome. She also continues to be a Senior Associate Research Fellow at National Taiwan University's Center for East Asia Democratic Studies and The Habibie Center, as well as a University Fellow of Charles Darwin University. Her latest book (with Greg Lopez) is entitled ‘Regime Resilience in Malaysia and Singapore’. She is following the 2018 campaign on the ground and providing her analyses exclusively to Malaysiakini readers. She can be reached at bridgetwelsh1@gmail.com. -Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.