For many Malaysians, Masjid Negara’s most striking feature is its umbrella-like roof as seen from outside.

This is understandable, with the exterior being aesthetically striking and uniquely Malaysian. Yet the focus on the exterior can take attention away from the mosque’s interior.

From within the prayer hall, one feels that the umbrella is not merely a national icon, but a spiritual symbol. The Qur’anic verses, embossed in gold, are the umbrella’s focal point, a calm structure peacefully descending over the worshippers. The umbrella conveys a sense of shelter, stemming from the luminous words of divine revelation.

Just as the exterior conceals the interior, the present often clouds the past. Current racial and religious tensions blind us to the fact that, not so long ago, this major Islamic structure was built as a collective national effort.

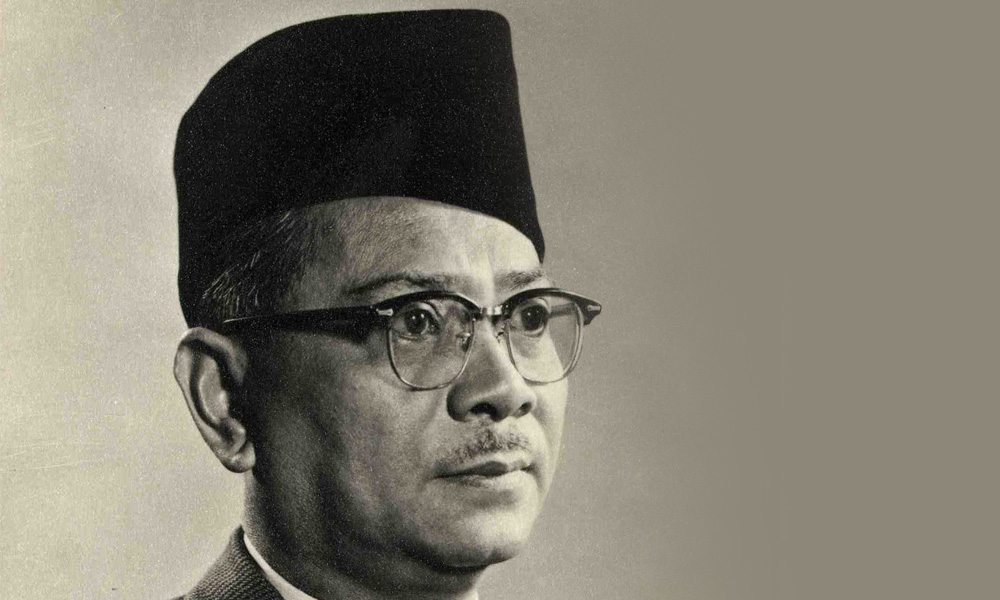

In his attempt to raise funds for the structure, Malaysia's first prime minister Tunku Abdul Rahman (photo) appealed to all Malaysians to finance the remaining construction of the mosque. His efforts were successful, with an old mosque brochure stating that the mosque was “designed by a Malay, constructed by Chinese and Indians, and financed by Buddhists, Hindus, Christians and Muslims.”

A space for Islamic worship, meant to bring Muslims together in prayer, was also a means for bringing Malaysians together as a family.

It is fitting that Tunku played a key role in Masjid Negara’s (above) construction. The mosque is a microcosm of his model for Muslims in Malaysia.

By a “model for Muslims”, I am not in any way implying that Tunku had any coherent project that he wished to impose upon the nation or the Muslim community. Nor do I mean that Tunku suggested any sort of “reform” or “development” to alter Islam.

Rather, Tunku organically applied traditional Islamic principles to the unique environment of post-independence Malaysia.

For Tunku, as for his friend Mubin Sheppard, building a Muslim community and building a happy Malaysia were not conflicting objectives.

On the contrary, these objectives informed each other, with Tunku and Sheppard seeing Islam as a force that could unite rather than divide.

As far as I am aware, Tunku had no coherent blueprint for Muslims in Malaysia.

But if I can have recourse to the imagination, I would picture Tunku in his residency at the Malaysia table – the one from the 1963 agreement – creating the blueprint for a mosque.

In addition to his pencil, ruler and architectural plan on the table, there would be a prayer mat next to him on the floor and a football.

“Why the prayer mat?” we ask. Tunku would probably smile and say, “Unless man is reminded of his duty to God, he will never think of his fellowmen”.

Why the football? Well, religion is about moderation; “We (Muslims) need to have a balanced approach to this world and the hereafter”. He may also laugh and say, “Human beings must have some fun some time.

he foundation

Tunku shows us his process over tea, which includes a plate of Yorkshire pudding (there is a side table in this scenario). He begins by showing the mosque’s most important section: the foundation.

This foundation is not one of stone, but of ideas. The central concept of this foundation is the notion of brotherhood.

On one level, Tunku’s model emphasises the brotherhood of Islam, the forging of bonds of love on the basis of faith.

For Tunku, “One of the greatest assets of the religion of Islam is its claim to the brotherhood of Islam, irrespective of race or colour”.

He hands us a beautiful green book – he gleefully tells us it was “pirated” at his own expense – called 'The Religion of Islam' by Maulana Muhammad Ali. The book explains how prayer unites people, through recognition of the unity of purpose and equality.

The Ka’ba acts as a focal point, indicating the “unity of purpose … (that) forms the basis on which rests the brotherhood of Islam”. The prayer levels social differences by making all people stand “shoulder to shoulder”, equal before God. The result is “brotherhood, equality and love”, created on the basis of faith.

On another level, Tunku’s model emphasises the brotherhood of humanity. Far from cutting off one’s relationship to other human beings, Islam emphasises that all of us are children of Adam, with the Qur’an asserting: “Mankind is a single nation” (2:213).

Fanaticism – blind and arrogant elevation of one’s own community – has no place in Tunku’s model, with Tunku asserting that “Islam stands for peace and goodwill among men”.

This goodwill involves recognising that Islam’s values – such as “peace, love, [and] co-operation” – are “human virtues” that “are accepted by all decent men, irrespective of race or religion”.

Tunku cites Malaysian Buddhists as an example: “Our Buddhist friends are striving for the spiritual upliftment of their followers, making them worthy and loyal citizens contributing to the peace and tranquility of our nation.”

Though we nod in agreement, there is a voice in the back of our minds telling us that principles need to be applied. The foundation is secure, but where is the building?

Reading the worry in our stuffed faces – we have been absent-mindedly helping ourselves to the puddings – Tunku points us to the mosque’s structure, built upon the principle of brotherhood.

The structure consists of the many institutions Tunku built through his Islamic welfare work, mostly after his premiership. Like Masjid Negara’s central prayer hall, these institutions are a calm place of repose, an open umbrella that shelters all.

Under an umbrella

In line with the brotherhood of Islam, Tunku’s structure shields and assists the marginalised sections of the Muslim community.

Chief amongst these groups were Muslim converts. Though they had entered Islam, racism served as a barrier that prevented – and still prevents – entry into the structure of the Muslim community.

Tunku noted the double alienation Muslim converts faced: they were “not only lost in the society to which they once belonged,” but “also lost in the society where they now belong – the Muslims”.

Both Tunku and Mubin Sheppard worked systematically to break those barriers down. In the years of his premiership, Tunku would use his own residency as a place for conversion ceremonies, as well as for converts to come and break the fast during Ramadan.

After leaving office, his work became far more extensive. Tunku addressed the issue of converts' education, organising a club for converts in Penang that would also have doubled as a support system.

The Muslim Welfare Organisation Malaysia’s (Perkim) publications were printed not only in Malay, but also in English, Chinese and Tamil.

Tunku was insistent that converts not feel alienated from their cultural identities: “In carrying out our work, it is very necessary for us to separate Islam as a religion from… Islam as belonging to any particular race”.

Under Tunku, Perkim’s work widened to a variety of social issues, from drug addiction to the Cambodian refugee crisis. We should also note that Perkim went beyond catering exclusively to marginalised Muslims.

Tasputra Perkim, an organisation dedicated to providing care for disabled children, was described by Tunku as catering to “handicapped children of all nationalities and religion(s)”.

While most of the funds came from Bakti members, Tunku’s support for the project and his willingness to allow it to bear his name – Putra – is a stamp of approval for the organisation’s cause.

Moreover, Perkim also had free clinics that were open to all, irrespective of race or religion. Much like the construction of Masjid Negara, financial support for Perkim came from Malaysians of all faiths.

This is not surprising when we consider some of Tunku’s stated aim for Perkim: “to make Malaysia our home and the object of loyalty of all people who live here”.

Leading by example

The call to prayer breaks our conversation with Tunku. He excuses himself for a moment, unfolds the prayer mat and begins to pray.

Seeing him in prostration, one realises that Tunku does not stop at creating a blueprint for a mosque. He engages in sajdah (prostration), the act that defines the masjid, a place of prostration.

Tunku did not merely speak of brotherhood, be it between men of faith or as part of the human family.

Speaking of Tunku’s virtues, Lim Yew Hock writes: “Above all his greatest virtue is that he is human and humane with a great understanding and sympathy for human frailties”.

Rather, he embodied that principle through his actions. A key example of this can be seen in his work with drug addicts.

Having been invited to speak to the boys at a rehabilitation centre in Ipoh, Tunku remarks on the inner conflict he experienced. This was not due to self-importance but sensitivity; “Lecturing them is like adding insult to injury, and nothing is worse than that”.

His advice to them was non-judgmental in nature, with Tunku advising them how faith gives one “the will-power and strength necessary to fight this evil”. The religious teacher Tunku selected for the boys was a recovered addict himself, providing the inmates with someone who could identify with their experiences.

We are nearing the end of our session with Tunku. Tea is over; his prayer is complete. Our host bids us farewell, taking the mat (and football) with him as he heads out the door.

A storm, steadily brewing whilst our architect was at work, bursts into the residency. The tea set crashes to the ground. But the scattered porcelain is nothing compared to the mess of new plans, with ideologies, political projects and outright fanaticism littering the Malaysia table.

The ever-increasing heap makes one lose sight of what we once saw so clearly. With such a depressing mass before us, one is inclined to leave the Malaysia table neglected, gradually weathered by each new storm coming its way.

Can we ever retrieve Tunku’s model from beneath the ideological mountain? I believe we can, though there may be some digging to do.

Tunku’s model is rooted in timeless principles, above the confines of any particular age. The question is less about whether the model can be retrieved as to how it should be uncovered.

Perhaps, as with Masjid Negara, our appreciation of Islam and Tunku’s legacy requires some reorientation: a shift from the outward to the inward. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.